The grotto is not big, and Na-Yeli has to make a sharp turn to avoid crashing into the ceiling. Not sure if there was enough room inside this crystal grotto for hang-gliding, she prepared two crystalline platform soles rather than the more extended landing gear she had used the previous time. She glides down and slowly lands on her feet. There’s a soft crushing sound as her crystalline soles compress and break the hyper-fractalized ground, which can’t be helped.

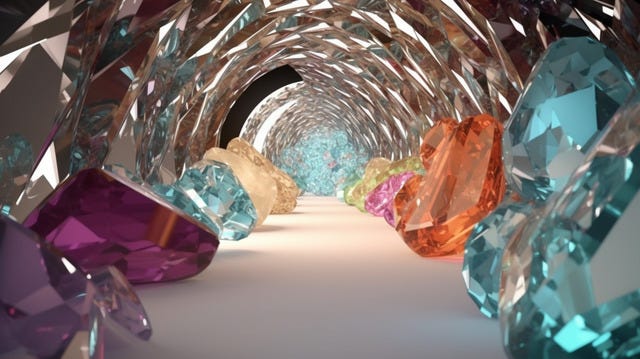

Na-Yeli hoped she could glide through this layer again, like the previous time. The crystalline materials are not solid with highly fractalized outgrowths but are—as far as she can discern—mostly hollow, three-dimensional structures, repeating themselves at smaller and smaller and smaller scales. A dizzying mix of fractal octahedrons, Sierpinski triangles, Penrose tiles, L-system trees, hexaflakes, fractal flames, and Mandelbulbs. As such, they contain a considerable amount of this layer’s N2 atmosphere.

After her outer cameras have adapted to the correct frequencies and intensity levels, Na-Yeli notices that—like the previous time—there is light in this crystalline layer. Possibly also generated by processes like piezoluminescence, triboluminescence, phosphorescence and fluorescence. No trace yet of the constant lightning that flashed between the lower and upper crystalline layers the previous time she was here. Possibly, Na-Yeli has to proceed through one of the three tunnels that converge on this grotto. If the three-dimensional crystalline fractal housing is predominant throughout this layer, then it’s very well possible that the lower and upper crystalline layers have merged, and tunnels are the only way through them.

On the one hand, that would slow them down quite a bit, as Na-Yeli can’t hang glide in these constricted spaces. On the other hand, the same rules—the ‘touch-the-wall’ and ‘Pledge’ solutions—should still apply. The shortest possible route between the North and South Pole in this layer is about one hundred kilometers, which would take her about twenty hours at a leisurely walking pace. However, if these tunnels snake around a lot, it might very well be a thousand kilometers or more, which will take her some two weeks, sleeping periods included. But, before she sets off, she wants to study this environment some more.

Watching it more closely, Na-Yeli finds that there’s a strange quality to the light. Not the crashing and ever-splintering reflections that echo the lightning she remembers, neither the more constant emissions of piezo- and triboluminescence, but something other, something more chaotic yet more controlled. As if most of the light is redirected through the hyper-structured crystalline grotto walls rather than passing through it. Almost as if these walls are alive, Na-Yeli thinks, maybe I’ve been in here too long.

Which tunnel to take first? There are three, all looking equally promising (or foreboding). She could use her Kittis. Program them with the maze rules, let them fly somewhat under half their range, and then let them report back to her. Their energy expenditure per kilometer is also a tiny part of Na-Yeli’s, so that might be an excellent way to start.

Then, in which way to move? Walk or improvise a ski or skate-like movement? Maybe she could decide that depending on what her drones report. Sometimes, she thinks, a CEO must know when to postpone a decision. The biggest problem is, like the previous time, knowing where she is. The static electricity in the crystalline structures wreaks havoc with the fast-rotating magnetic field of the naked singularity, meaning she doesn’t know magnetic North nor magnetic South, making dead reckoning very hard as she can trust only her mini-gyro-compass. Her lidar and sonar are unusable here, as they get completely scattered. Radar works a bit better but can only discern fifty to one hundred meters into a tunnel before it disperses.

Therefore, her Kittis may be a better guide. She selects three of them and then launches each into its designated tunnel. With their batteries fully charged, they have a reach of about eleven kilometers, so she’s programmed them to return after five. In case the tunnel branches off, she’s programmed them to choose the right-side tunnel (‘touch-the-wall’ on the right side). They should be back after about ten minutes.

Ten minutes later, they come back, two reporting three branches, one four. It looks like it’s going to be a maze, indeed, Na-Yeli thinks and selects one of the two tunnels with only three branches in the first five kilometers. The tunnel walls all have unique distributions of the various three-dimensional structures, even if recording that takes up vast amounts of memory space. The DNA-structured ghost disks of her triple-redundant quantum computer have stupendous amounts of memory space available—hence it was no problem to provide a virtual world for the hypersounders—yet accessing all that memory will take more time as more memory amasses (while the hypersounder simulation runs on a self-maintaining part of these ghost disks).

Then again, Na-Yeli will only move at walking speed, giving the system plenty of time for pattern recognition and comparison. She also notices that the Moiety Alien has been quite inactive during her musings and Kitti launches, hovering near her, not moving at all. Is it politely waiting for me to make up my mind, Na-Yeli wonders, or does it also not have a clue how to traverse the maze? Nevertheless, it did come through it on the way in. One final thing to do before she commits herself.

“OK, crew, update,” she says and explains the situation as clearly and succinctly as possible.

—the hypersounders wish to know how long this will take— the communication AI signals.

“Impossible to say, as I don’t know how hard or easy this tunnel maze will be,” Na-Yeli says, “but I’d estimate two days if all goes extremely well until one month, or possibly longer if they go horrendously slow.”

—that’s like solving a slow-motion soundscape, the hypersounders say— the communication AI signals —they ask to be held in suspension, or at least slowed down maximally until this boring layer is done—

“I could say certain things about their attention span, but because of their good services in the past, I will not,” Na-Yeli says, “do you wish to be kept on?”

—no, i agree with them— it signals —put me back on when there’s action—

Na-Yeli shrugs, freezes, and backs up the hypersounder simulation, then switches the communication AI off. Well, more energy for my Kittis, she thinks, even if she realizes it’s not much. She gestures to the Moiety Alien and walks into the tunnel she’s selected, crunching delicate crystalline structures underfoot.

The crushing noises of trampled crystal fractal flakes have a slightly melodic, almost cymbal-like tone. As such, it becomes a pleasant background melody rather than an insistent whisper that Na-Yeli’s destroying very delicate structures. The soothing sound negates her nagging conscience as she makes her way through the seemingly endless tunnels. Yes, she’s only one-fifteenth of her normal weight in here. Yet it’s still enough to pulverize the most finely branched structures, which, like her previous passage, are indeed self-similar all the way to the molecular level—she analyzed a few pieces.

After the first five kilometers, she sends out three Kittis again, one programmed to keep to the right, one to keep to the left, and one to follow branches at random, and all to return after five kilometers. All of them report three to five branches, four on average. Since none of her navigation tools are reliable in this layer, even her best ‘dead reckoning’ software slowly gets lost. She’s but all too clearly aware of the ‘touch-the-wall’ rule that—combined with the ‘Pledge’ functionality of recognizing places where she’s already been—has gotten her through this fractal maze the first time. This time, though, it’s not a huge, roughly shell-shaped grotto with stalactites, stalagmites, and merged columns but rather one huge fractal underground veined with tunnels.

While the gravity is a measly 0.075G, she can’t fly through here because the tunnels are too small. She has to duck her head quite often and crawl on her belly a few times, necessitating the production of crystalline gloves and belly shields. This is definitely not a place for those who have claustrophobia.

At some point, it becomes pointless to send out any more Kittis, as they do not seem to find anything out of the ordinary. She tried to make a map of their paths, but since all the tunnels curve ever so slightly in all directions, the dead reckoning software loses sight of their positions, and the recorded paths either diverge more than they possibly can or even cross each other—which is not impossible in this almost fourteen-kilometer thick layer, but also not very helpful.

The slow progress gets on her nerves. She has no idea where she is, let alone if there is an exit to this maze. She’s afraid that sticking to the right wall will lead her back to the beginning and thinks sticking to the left wall has the same possible effect. Yet LateralSys’s rules tell her to stick to her choice, as choosing branches at random has a much bigger chance to lead her astray, and—according to Probability Theory—will almost certainly take more time to cross the maze than sticking to the rules.

It’s incredibly frustrating. She might be walking around for weeks, possibly months, before she finds the exit. And she’ll only know when she’s near it when she sees it. In the meantime, her progress is slow, mostly walking with the odd belly crawl. She doesn’t know what to do if a passage becomes too narrow for her and decides she’ll work that out when it happens. After eight hours, it’s already becoming quite monotonous, and she has no idea how mind-bendingly tedious it’ll become after several days, let alone weeks.

So, she keeps her mind busy by trying to figure out a way to move faster. Any form of skating and skiing is not feasible, as the bottom of the tunnel is too uneven. Long step-jumps—possible in this low gravity—are also unfeasible because the ceiling is too low most of the time. Sometimes, the tunnel does get higher, but only for a short stretch, nothing that would gain her much. On top of that, sometimes the tunnels make sharp curves and unexpected twists, meaning she must brake fast before those or crash into them, puncturing her exoskin. So even if she could go more quickly, it might be too dangerous.

Try as she might, she can’t work it out and keeps progressing as boredom overcomes her. After eight hours, her mind is numb. After ten hours, she’s close to entering a vegetative state. After twelve hours, she’s jealous of zombies. After fourteen hours, she almost is a zombie. After sixteen hours, her body is still not tired—thanks to the minimal gravity—but her mind is utterly exhausted. Exhaustion was one thing she saw coming, and in her last hour, she could keep going because she was designing a crystalline backpack-cum-sleeping-bag in which she is going to sleep. Her reward for the day.

The next day, she starts afresh, but after several hours, she slowly yet inevitably crosses the edge of tediousness. Surreptitiously, she’s becoming jealous of the communication AI and the hypersounders, who can skip the boring parts. Then, a more willful part of her wonders if she can program the communication AI to take over her limbs while she hypnotizes herself into an induced coma. Tempting though it is—especially after another eight hours through these endless tunnels—she’s too conscientious to trust all their lives to a mere computer program. So she soldiers on.

Near the tenth hour of the day, she’s becoming so numb she starts to experience hallucinations. At least, that’s what they’ve got to be, as such strange beings can’t be real. Just look at them: crystalline byrds not with wings but with a small propeller, hovering while having a very long beak not unlike woodpeckers with which they, indeed, seem to peck parts of the tunnel wall’s delicate structure. Give her the control over a few hundred of these byrds, and she’d command them to drill her a tunnel—an express subway—straight to the South Pole.

Uncomfortably numb and extremely light-headed, she tries to tickle the cute little byrdie on its blue belly, away from its rapidly turning propeller. It doesn’t like it and aims one of its lightning-fast pecks at her hand, its razor-sharp beak cutting into Na-Yeli’s hand right through her exoskin. The immediate and intense stab of pain is almost like a welcome wake-up call. It hurts like hell, but also awakens her from her stupor and breaks the monotony.

“Ow!” She says. Wow, she thinks, that byrd is real.

And it’s not alone, further up Na-Yeli spots more of them, pecking—seemingly at random—at the tunnel walls. They’re beautiful, Na-Yeli decides while her hand still stings. Yet byrds with propellers, that can’t have evolved right? But if they haven’t evolved, who or what designed them?

In more mundane matters, maybe they have a nest? Or a sleeping place they return to? Na-Yeli decides to link two of her Kittis to two, well, Crystalpyckers, and follow them for five kilometers if they move away from this part of the tunnel. Na-Yeli cannot go far away, otherwise her Kittis cannot get back to her. She doesn’t mind as she has been going for a mind-numbing ten hours and welcomes an earlier rest. This startling discovery warrants it, in her opinion.

She watches the Crystalpyckers for an hour or so until that also becomes, well, boring. She unrolls her backpack-cum-sleeping-bag, and calls it a day.

Support this writer:

Like this post!

Re-stack it using the ♻️ button below!

Share this post on Substack and other social media sites:

Join my mailing list:

Author’s note: back from being offline for about a week. It might have been refreshing, if not for the fact not much else was happening on this ferry that was being transported by a delivery crew from the newbuilding yard in China to Santander in Spain, where the the rest of the original crew boarded (I boarded in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, with the original bridge and engine crew, who I trained in our equipment). I did write a bit on board, but not quite as much when I’m staying in a city with parks, coffeeshops and good restaurants.

A vibrant atmosphere uplifts my writing, while a dull atmosphere represses it (somewhat). It’s why I’m trying to avoid tedious locations1 if possible, it’s why I like inspiring scenery in nature while basically being a city boy2. In any case, good to be back and many thanks for reading!

For your idea about ‘tedious’, of course. What I find uninteresting may very well fascinate you;

Who is willing to go to pretty isolated deserts to witness a solar eclipse;