Forever Thrilled, Part 20

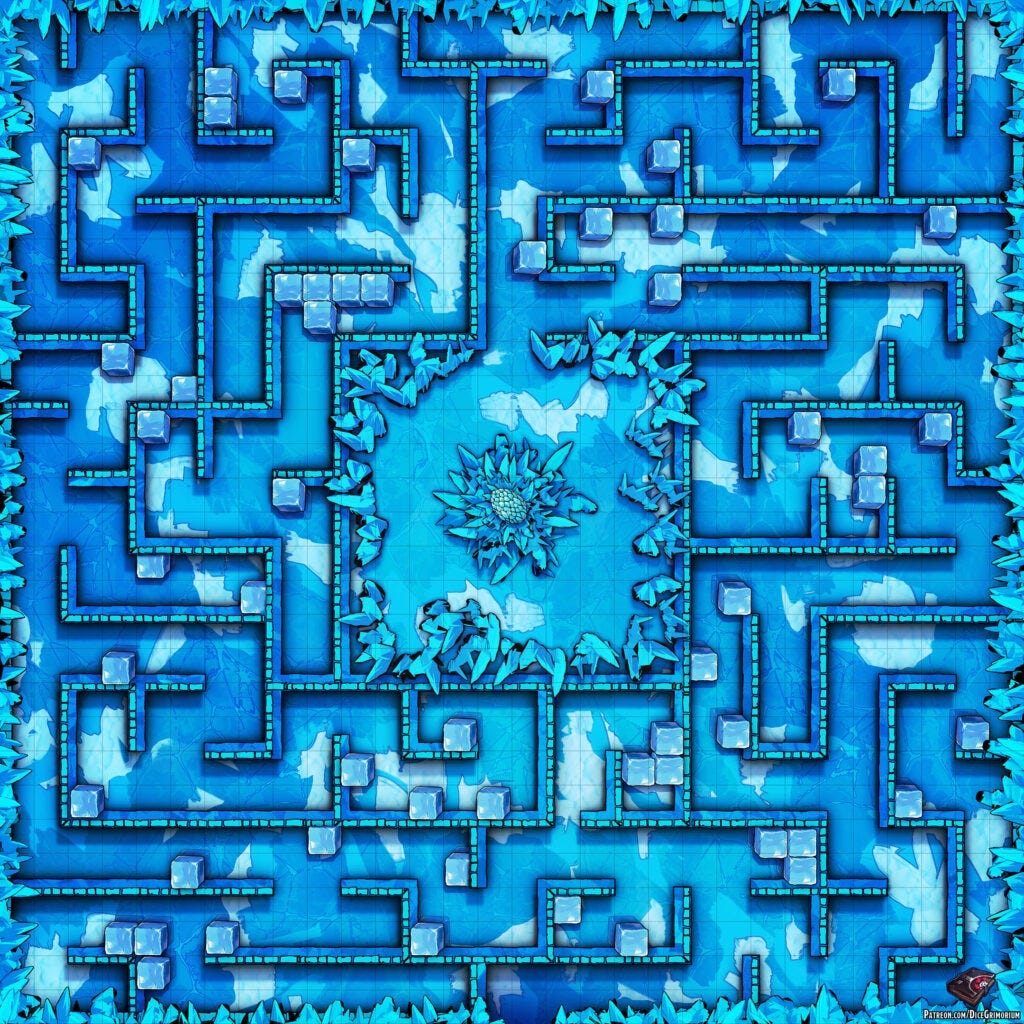

Chapter 6: The Fractal Underground

Ten hours later, she wakes up. She tries to contact her two Kittis, only to find they’ve moved only a few hundred meters further into the tunnel. She stretches, has whatever recycled stuff there is for breakfast, and heads in their direction. Some four hundred meters onwards, she finds the flock of Crystalpyckers going at their business.

There are two possibilities, Na-Yeli thinks, either these byrds don’t sleep, or their sleep cycle is way out of sync with mine. How can she find out? Stay here for another twenty-four hours or so? It probably won’t make much of a difference, considering the amount of travel she still has to do (without knowing how much real progress she has made). On the other hand, her conscience is an impatient mother, nagging her constantly if she isn’t actively doing something. Yet she thinks it’s worth discovering, her curiosity overcoming her lingering doubts for the moment.

So she waits and waits, and eventually the waiting becomes just as bad or worse as continuing her slow march through the tunnels. The Crystalpyckers keep on going at whatever they’re doing. Feeding? They do seem to know what they’re pycking at and what not. Na-Yeli can’t quite find out which parts of the fine-structured tunnel walls they prefer, though, as she compares tunnel walls that have been left untouched with those that the Crystalpyckers just passed.

She doesn’t see any difference, nor can her pattern recognition software discern any order in this chaos. The only system Na-Yeli’s seeing is that the propeller avians—a flock of twenty-four byrds—gradually make their way through the tunnel, at a pace much lower than Na-Yeli walks, seemingly covering every piece of these walls.

The how and why of it completely escapes Na-Yeli, who finds herself increasingly under pressure—call it explorer’s guilt, call it self-motivation—to carry on with her trek into the great ennui. Neither of her options are very attractive, to say the least, but she still resists the urge to plow onwards through these corridors of apathy. These byrds can’t go on forever, right?

Two hours—one hundred-and-twenty minutes of being torn—later, she gets her answer as the pycking activities stop and the byrds hover down into a huddle and go asleep. Now she wants to get to the bottom of it and decides to sleep at the same time as them, aiming her motion sensors at the huddled byrds as she programs them to wake her when they start moving again. Sometimes, she thinks, sedatives are your friends, as she goes under.

Eight-and-a-half hours later, the motion sensors wake her up. The byrds are active and move to their respective positions on the floor, walls and ceiling. How they divide the food—or the labor, who knows—she can’t say, only that it goes with an ease that betrays an ingrained routine or a deep evolutionary trait. She watches it for a good hour or two and then figures that she is not learning much while she’s moving even slower than before. Quite probably, we’ll run into another flock at some point, she thinks, but how do I know they’re not the same byrds? So she programs three of her Kittis—who are much smaller than the crystalpyckers—to paint a crimson ‘N’ in the middle of their blue bellies.

I didn’t see ‘Kilroy was here’, Na-Yeli muses, so this is short for ‘Na-Yeli was here.’ Then she takes a deep breath and goes on her way, carefully passing the Crystalpycker flock who were already moving in her intended direction. A shame they don’t move faster, Na-Yeli thinks, it would have given me some distraction. Unfortunately for her, nothing distracts her for the next twelve hours, after which she calls it a night, mentally not quite that tired as thoughts and theories about the Crystalpyckers helped her pass the time.

The next couple of days pass without any excitement. Na-Yeli gets up and has the same foodstuff she has at lunch and dinner but calls this ‘breakfast,’ then rouses herself to continue on her way. She sticks to the right wall, constantly comparing it with previously recorded stretches, but finding no matches, which should be encouraging: either she’s not following a loop or one so big it might pass the South Pole, anyway. She has a voice assistant reading her parts of the physics and mathematics that the alter-Universal aliens sent her, but—missing LateralSys’s brilliance—can’t make heads nor tails of it. She tries to expand the ‘gesture-cum-movement’ language she’s developed between her and the Moiety Alien, yet it remains at a stage where it’s OK to use for short, decision-making events, yet way too rudimentary for a serious talk. It’ll take many months, probably years, before we can exchange anything like deep thoughts, she thinks, and forget about philosophy.

She makes the voice assistant read exciting adventure tales, which helps for a while until the contrast between the amazing stories and her utterly uneventful plodding becomes but all too clear and frustrating. On the fourth day, she runs into a dead end. She’s had to scrape through one tunnel the day before, barely getting through—even if the Moiety Alien in/deflated through it in no time—and wondering what to do if a tunnel really becomes too narrow. She’s facing that dilemma right now, as the tunnel has narrowed so much there’s no way she can get through it without slicing herself up.

In the colorful, ever-changing light of these tunnels, it’s hard to see if the tunnel expands again, stays narrow, or even closes up. But she can send a Kitti through, which she does. It comes back quickly, reporting a dead end some six meters in. Na-Yeli has no choice but to return to her steps. Follow the wall until the next branch, she recites the rules inwardly, then keep following the right wall. The previous branch was some three kilometers back, but Na-Yeli’s barely keeping track as it is, slowly exhausting her ways of not getting bored.

On her fifth day, she runs into twenty-four industrious Crystalpyckers. None of them carries a crimson ‘N’ on their bellies, so they must be a different flock. She follows them for a full day, only to find they follow precisely the same routine as the previous ones. She marks them with a ‘Y’ and moves on.

Halfway into her second week, she’s running out of things to keep her mind occupied, as she slowly loses the will and the motivation to concentrate but has no choice but to move on. The days become indistinct and begin to fade into one great blur in her mind—thank dog her software keeps track of the time. She sees a strange shimmering in the distance, a flickering both uncanny yet eerily familiar. She pinches herself to make sure she’s not hallucinating, and her instruments tell her they also see a new pattern. It happens to be in the direction she’s traveling in, anyway, so she moves on.

As she comes closer to the source of the strange shimmers, it becomes apparent that they’re reflections from a tunnel in the left wall. According to the labyrinth rules, she’s not allowed to go in there. Na-Yeli stops for a split second, then thinks Fuck the rules, and walks into the tunnel.

Only a few meters in, behind a slight curve, Na-Yeli sees what’s causing the distinctive glimmering. Butterflies, big ones, she thinks, almost exactly like the Glassamer Butterflies I saw in my previous passage through here. All the Glassamer Butterflies are located at the very end of this short tunnel, a veritable wall of them at the dead end of this cul-de-sac. Breeding grounds? Na-Yeli wonders, a place to rest? Yet none of the glassy, transparent butterflies are hanging still. All of them are flapping their wings while, at the same time, they’re basically staying in place.

Na-Yeli looks at the wall of writhing butterflies and feels like she’s not seeing something right. These transparent wings and these reflections everywhere, she thinks, it’s like a hall of funhouse mirrors, like a massive trompe l’oeil. The visual information is so twisted, so weird that her mind—a pattern recognition machine par excellence—is trying to make sense of it, nevertheless projecting or superposing an image that is not actually there. Upside-down? No. Inside-out? Also not. Something’s pushing ... pushing ... pushing forward back. That’s it. She’s seeing the backside of all these butterflies while their wings are flapping forward, straight into, what must be, a tunnel wall.

That doesn’t make sense, Na-Yeli thinks, unless... She measures the average distance between herself and the center section of butterflies with her lidar, smoothing out the variations through an averaging filter. At such a short distance, without reflections and refractions, her lidar is exceptionally reliable and precise. She repeats the measurements over time, and—sure enough—the mass of butterflies is slowly moving forward. Their wings, which look as sharp and brittle as she remembers, are slowly excavating a new tunnel.

Which seems utterly pointless to Na-Yeli, but maybe it’s the only way in a world without dynamite. She waits a bit longer to be absolutely sure, but the lidar doesn’t lie: they are moving forward at about a millimeter a minute. At this pace, it takes about 700 days to excavate one kilometer of tunnel, Na-Yeli makes a quick calculation, probably more than two years if we take sleeping breaks into account.

More confirmation comes from other instruments. When the Crystalpyckers were picking, the silicate saturation levels in the Nitrogen atmosphere barely changed, according to the data her instruments recorded. Now they measure the presence of a fine powder, a very fine powder, alright. Like fine sand, the powder is somewhat heavier than air, even if strong winds or updrafts can carry it along for a while. But eventually, it will settle, even in this light gravity.

Well, she has to figure out their schedule, as well. So Na-Yeli stays in this cul-de-sac with the potential to become a through road in a couple of years. She stays there, watching the wall of butterflies recede—a bit like the reverse of watching grass grow. After a couple of hours, though, the activity stops, and the butterflies settle themselves at—for them—nice spots on the various walls and go to sleep. That’s seven hours earlier than the first flock of crystalpyckers, Na-Yeli thinks after checking the records in her board computer, synchronized sleep cycles, my ass. Each flock of avians seems to have its own schedule, independent from others. It sorta makes sense, as Na-Yeli also has no idea how sleep cycles could be synchronized in this world with its ever-dim light.

One more time, she forces herself to sleep. Some eight hours later, her motion sensors wake her as the Glassamer Butterflies converge on the far wall and restart their slow-motion excavation. Na-Yeli watches them for a while, wonders if she should mark them, but then decides otherwise. Chances are, there’ll probably be more of them, she thinks, but then again, what’s the point? She has no clue and decides to puzzle over it as she continues back on her way. It’s not as if she’s got no time to think.

For a while, she feels much better. The monotonous, keep-going-don’t-try-to-think days before she ran into the Glassamer Butterflies were wearing her down. So much that she started to wonder if she would ever make it out of here. On her tombstone: Na-Yeli, mistress of the Berserker Forest, double traverser of the unstoppable Strange Hail, rider of the Superswirl, finds her Waterloo, her queer nadir in intense ennui. But she’s not there yet. Not quite.

Her thoughts clear up for the first time in long, long days. Something was nagging at her, nibbling at her subconscious, as it were. But what? Something to do with the tunnel walls enclosing her and the Crystalpyckers and Glassamer Butterflies feeding—or whatever—on them.

On a hunch, she sends a Kitti back into the tunnel from which she just came, programming it to stick to the left (basically going back on her tracks), and then records the tunnel’s right wall very carefully—like Na-Yeli does all the time.

By dog, she thinks, the monotony anesthetizes my brain. If the Crystalpyckers and Glassamer Butterflies change the tunnels—no matter how subtly—then the tunnel system is not static. It gradually changes over time. Quite possibly, it grows and evolves over time, as the Nitrogen atmosphere is supersaturated with hot silicates that can condense anywhere, forming more fine structures.

The mini-drone returns, and she runs its recordings along hers, programming the pattern recognition software to compare them at the deepest level possible. At the highest resolution—close to the molecular level—comparison takes time, taxing even here state-of-the-art (at least, in her original timeline) quantum computers. Then the results come in.

More than 99.9% similarity in the first two hundred meters, but gently, yet irrevocably declining after that. The perfect match decreases to below 99.5% after the second kilometer and decidedly below 99% at the end of the fifth kilometer. The tunnel walls are changing, Na-Yeli thinks, slowly transforming beyond recognition.

Meaning she’s screwed because she cannot use her ‘Pledge’ system, so she has no way of knowing if she’s passed through a particular tunnel before. This ‘living’ tunnel system renders her labyrinth rules obsolete. I might be running around in circles and never know it, she thinks, frustrated and despaired. What now?

Support this writer:

Like this post!

Re-stack it using the ♻️ button below!

Share this post on Substack and other social media sites:

Join my mailing list:

Author’s note: hey, I didn’t have an ‘author’s note’ in the previous post. First time it happened. I though about filling it in afterwards, then decided against it, as it reflects what I’m doing.

A confession: I don’t like doing self-promotion. I know I need to do it—especially as an author with a contract with a publisher—but that doesn’t mean I have to like it. Same with proofreading and editing—I know they’re both necessary (evils), but they’re not—to sy the least—my favourite activities.

I’m a writer. I love to write. I experience great pleasure from the process of creation, from the act of putting a fresh narrative on the white page. The best—not the only—way for me to get into my creative zone is to be in a city where the daytime temperature is between 20 and 25 degrees Celsius (no rain), so I can sit on a shaded bench in a park typing away on my 15” MacBook Air (biggest portable screen to battery life ratio). A city because then a coffeeshop for a short break is always nearby, and some fine restaurants for dinner.

I accumulated a lot of holidays during this year, meaning I’m spending some on Lanzarote right now. Temperature varying from 19 to 24 degrees Celsius (excellent for the Northern Hemisphere winter) and my writing goes very well. Unfortunately, this means I’m less motivated to update this Substack, because I’ll have plenty of time for that when I return to the cold, wet Netherlands next week.

It goes so well that the the third novel in my ‘Consensual Reality’ trilogy—titled “The Constructors of Consensual Reality” will be finished this weekend (first rough draft, then the rewriting and editing begins). Then I’ll return my full attention to this substack.

It also means I’m somewhat jealous of writers who have a publishing contract. And I mean ‘only somewhat’ because—if my info is correct—the average advanc for a novel is about 5,000 euros (or dollars, pounds). I’m sorry, but that’s below—well below—the month salary of my day job. I can’t write, let alone sell, a novel a month so the chances of my writing paying the bills are remote at best (not that I keep trying, though).

It represents my dillema: if I could work less, I would have more time for self-promotion and suchlike. However, sales would have to rise pretty quickly for me to be able to pay my bills, otherwise I’d have to beg my employer to be working full time again.

And so I struggle onward. But the good news is that I have content for at least another three years. As always, many thanks for reading, and if you could spread the word that would be very nice!