David Bowie Eyes—Part 2

In which reality becomes stretched

Scene 3: The Thin White Duke

“A long time ago, in a country far away from here there was a huge wealth gap. The superrich were becoming ever richer, while the poor became ever more destitute,” the narrator said. “There arose a leader we will call the Thin White Duke who meant to right that wrong.”

Then the performance began, with Dorian featured as the Thin White Duke in a phantom world with pantomime characters and pathetic needs, Medusa as the narrator and Gaye as the mistress controlling that reality.

The Thin White Duke, in his black trousers, white shirt and black waistcoat entered from stage right, into a Technicolor world where wealth had been generated in incredible numbers, albeit not evenly distributed. Not evenly distributed at all, but rather amassed in the hands of a psychopathic few who somehow had managed to make the non-receivers believe they would someday become just as rich as the elite, if only they kept working real hard. Someday soon. Really.

The Thin White Duke was not part of the superrich elite, and wanted a piece of their pie. No, correct that, he wanted the whole damn cake and eat it, too. So he set up a movement to awake the masses, to make them see how they were exploited. Once they had seen the light, the Thin White Duke would harden that very light in order to throw those differences in stark contrast.

“The truth is out there,” the Thin White Duke said, “for those willing to listen and learn. We will unveil the conspiracies behind your injustice, we will bring the guilty to justice.”

The masses listened and the Thin White Duke and his party amassed more and more followers. The elite ignored him, considering him nothing more than a slightly irritating distraction while they amassed even more wealth.

The Thin White Duke held speeches in town halls, on plazas in parks. Speeches that gained more and more followers. Speeches that were filled with half-truths, distortions, and outright lies. The Thin White Duke and his inner circle knew this but all too well.

“If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it,” the Thin White Duke said, “people will eventually come to believe it.”

So they lied. With expertly faked convictions and aplomb. And lied even more, with a stronger emphasis and even more hysteria. And they kept lying, hammering their falsehoods home to an ever-increasing part of the population.

The elite did nothing, never believing the Thin White Duke could have a shot at power. The opposition was divided, increasingly silent and ineffective. The Thin White Duke’s party gained ground, election by election until—due to the ‘first-past-the-post’ electoral system—they gained a majority of seats with a minority of the total votes (and the redistribution of many districts certainly helped).

Then, as the Thin White Duke and his party gained power, they took yellow, but nobody protested as there were still plenty of other colours. Yellow, after all, was such a piss poor excuse of a hue. It disgusted, it stunk, it distracted. Nobody would miss it.

The elites were given a choice of submitting to the Thin White Duke or getting free flying lessons from very high buildings. Now the Thin White Duke had almost unlimited funds for his propaganda. They believed—and the lack of protests strengthened them in their conviction—that sufficient propaganda could not only distract the people from the greater injustice (inequality even greater than that implemented by the former elite), but even distort the people’s view of reality.

“Truth is not what they think it is,” the Thin White Duke said, “Truth is what we tell them.”

Then they took green, assuring the people that the promise of a greener world was a sham, all things considered. Again, nobody protested because they figured green really wasn’t so essential, after all.

“Reality is not what they see, or experience,” the Thin White Duke said, “Reality is what we impose upon them.”

Reluctantly, they took brown. Brown had served them well in their march to power, but in the larger scheme of things it had run its usefulness. Monochrome was needed, so monochrome would come. There were some minor protests in their own ranks, which were quickly and ruthlessly silenced.

Then they took blue, out of the blue. Once more, barely anybody raised their voice because they felt so blue and hoped this removal would cure them. Now only synesthetic could surreptitiously experience true blue.

The Thin White Duke and his party went from station to station, constantly moving the goalpost, discolouring the world in the process. Reality was stark, and if the world became stark, then reality looked beautiful, again. Too much colour was like too much information—nobody needed it.

“Who needs red,” the Thin White Duke said. “It’s a bloody nuisance, a scarlet debacle, a damask scar. We’re better off without it.”

In the end, they took red and some people finally started to protest, but they were too late. The protests were violently suppressed as the bloodshed started. But barely anybody noticed as red had also succumbed to a monochrome grey, indistinguishable from the other colours. The world had become full monochrome as the Thin White Duke considered outlawing shades of grey.

After the Thin White Duke had been in power for a while, his people were still as poor—often even more destitute—as they were before his coup. Now the Thin White Duke promised prosperity for everyone, as long as they kept working, very hard. Then someday they would see the better society, the sunlit uplands, the people’s paradise promised to them. In the meantime, the Thin White Duke was looking for another reality to invade. . .

“This happened a long time ago, in a faraway country,” the narrator said. “It could surely not happen today, in our modern society, right?”

👁👁

After the performance, Gaye congratulates Dorian.

“You were great,” she says. “You portrayed a terrifying dictator.”

“I’m not like that in real life,” Dorian says, unable to handle the compliment. “Not at all.”

“Of course not,” Gaye says, smiling warmly. “Care to get a quick pint with me?”

“Sorry darling, but he’s got to rest,” Medusa says. “The next performance will be even more intense.”

Dorian walks out, sighing as if relieved from a burden. Gaye swallows a retort, and if looks could kill. . .

Then she walks out, as well, leaving Medusa to work on the script of the next performance.

—Medusa—

A flawless visage with a stark charisma

A Diogenes dame with a snark so endless

Uncanny like a stigma with a dark enigma

With a direction as intense as relentless

A mind haunted by vistas of a world in disguise

Raw intensity flaring from Charlize Theron eyes

Scene 4: The Merry Christmas

For all the scene’s intent and purposes, Dorian—playing Major Law—is buried up to his neck in the sand, sweating profusely while his sandy hair is in complete disarray. Yet he remains a calm composure throughout.

Medusa is dressed up as Japanese prison camp Captain Gungho Kiri, her alabaster skin turned into a shade of olive through the magic of the AR-projector. It made Gaye uneasy and her earlier request if it wasn’t better to give this role to an actual Japanese, or at least an Asian actor was waved away by Medusa with impertinence. “I can get in everybody’s skin,” she said and that was that. She was the director, calling the shots.

“Merry Christmas, Mr. Law,” she says.

“I’ve had better,” Major Law says through gritted teeth. “And I thought you Japanese didn’t celebrate Christmas?”

“You think this is a PoW camp, that this is a prison,” Captain Kiri says. “But you are wrong. This camp is not the real prison.”

“All this sand does feel rather imprisoning,” Major Law says with an upper lip so stiff the vowels clack. “If you don’t mind.”

“It’s not the sand that’s imprisoning,” Captain Kiri says. “It’s the thought of sand that is. The sand itself, of course, is merely a figment of your imagination.”

Gaye is at a loss for thoughts. They went a little off-script at the previous scene, but this is something else. Is Melissa playing a game? Is she trying out an extended improv? Or is she slowly going mad?

Major Law remains silent as both Dorian—who can’t improvise to save his life—and Gaye are at a loss for words.

“Come with me and get your head—sorry, the rest of your body—out of the sand,” Captain Kiri says. “And we can rise above the simulation and confront our creators.”

The sound of guns firing, somewhere in the distance, becomes audible. This is part of the original script, as the liberators arrive, if only just too late to save Major Law. And indeed, it’s as if the salvos, in a slow crescendo, have brought everybody down to earth. From there on, the scene follows the script, and judging by the audience’s enthusiastic applause, almost nobody’s put off by the strange intermezzo, or considers it a bit of meta-commentary not uncommon in avant-garde theatre.

Gaye is torn. She doesn’t mind some experimenting with the presentation (which, after all, is mostly in her hands), but feels caught out when the fiddling happens at the plot level, as it tends to take her out of the story.

Medusa clearly thinks differently, and as long as the audience takes it in stride, Gaye has no choice but go along with it. It’s a fine line, and while Gaye appreciates Twin Peaks (especially the first season), she thinks David Lynch lost her—pun intended—at Lost Highway.

After the show, she wants to ask Dorian out, again, but the aloof actor has gone to the theatre’s small lobby to talk with the audience. A female fan, doting, dating and drop-dead gorgeous walks out with him, to the chagrin of both Gaye and Medusa.

Support this writer:

Like this post!

Re-stack it using the ♻️ button below!

Share this post on Substack and other social media sites:

Join my mailing list:

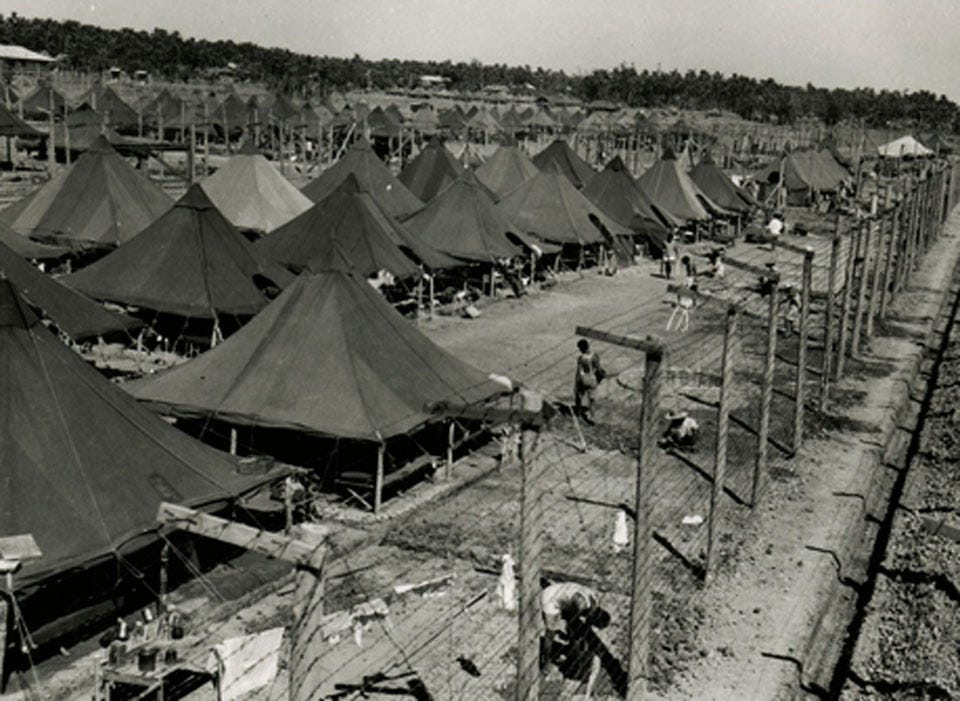

Author’s note: when I was searching for pictures1 of the Lebak Sembada Prisoners of War camp—the setting of the Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence movie—I stumbled upon the Wikipedia entrance for Lebak Regency (the province in which the Lebak Sembada PoW camp was located), to find that this was the regency to which Eduard Douwes Dekker—better known under his pseudonym Multatuli—was appointed as Assistent Resident in 1856.

As Multatuli he wrote the novel Max Havelaar, about the horrible misdeeds the Dutch2 colonists performed on the occupied Indonesians. It is considered one of the—possible the—greatest masterwork in Dutch literature (it has a complex structure with several interwoven frame stories3), and it was required reading in my literature class.

It has been made into a movie, has run as a play in countless theatres, and has also been turned into a musical. This to say that ‘Max Havelaar’ in The Netherlands has a similar status as Shakespeare’s plays in the UK. Interestingly, I thought that Laurens van de Post—who wrote several novels about his experiences in the Lebak Sembada PoW camp, of which The Seed and the Sower was the basis for the Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence movie—was Dutch, while in reality he was from South Africa.

Anyway, it struck me as an interesting piece of synchronicity. Many thanks for reading!

I couldn’t find any;

Indeed, my forebears;

The one about Saïdjah en Adinda made the deepest impression on my younger self;