The Simulation Hypothesis, Reprise 3

Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems

Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems are one of the most—possibly the most—influential and far-reaching theorems in mathematics. They have been proven (which is ironic, and more than a little bit paradoxical). The main question is: are they applicable to a non-mathematical system such as our reality? Let’s first explore these theorems and then see if they apply to the real world.

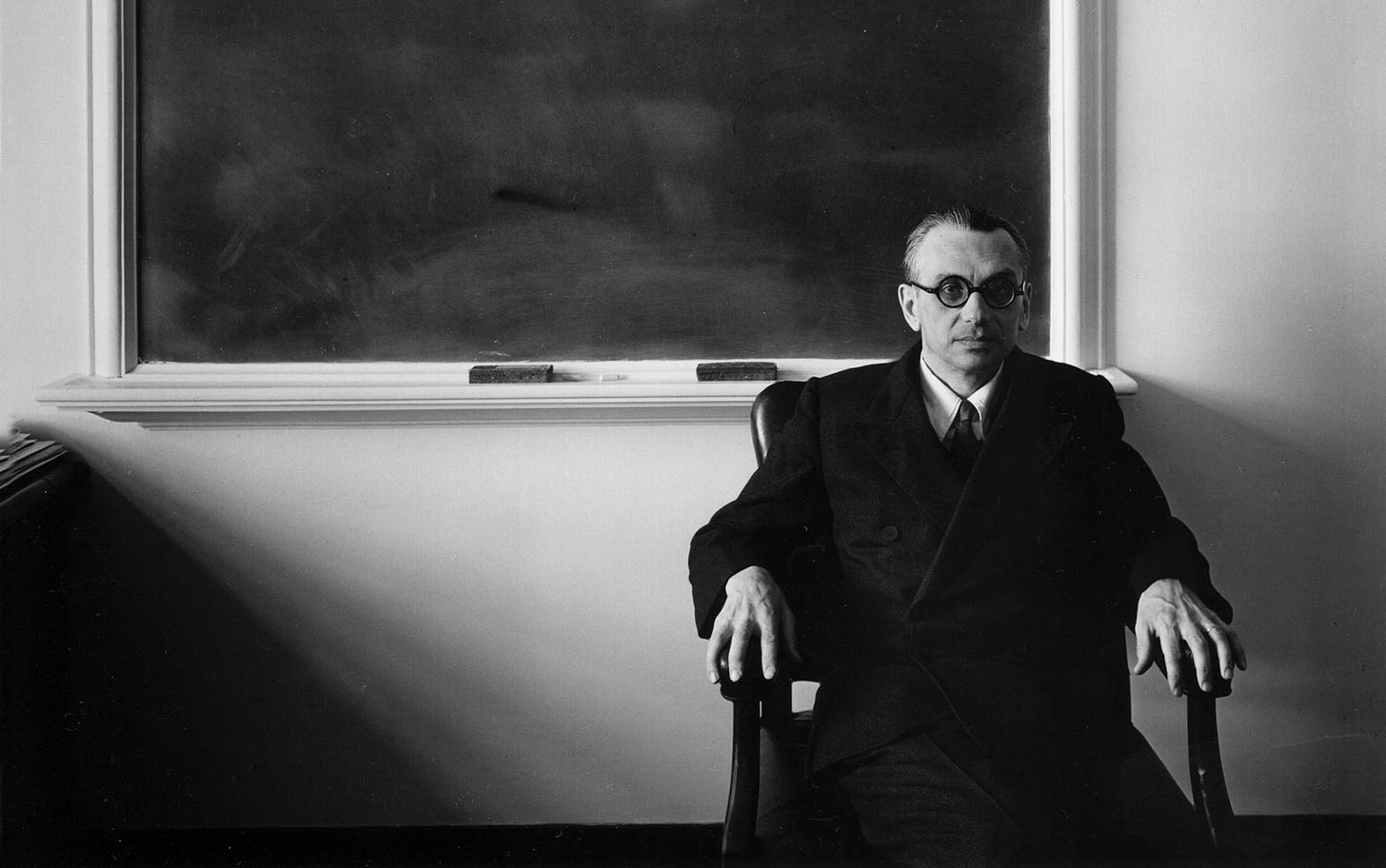

Kurt Gödel was a genius, but also a highly eccentric one. It’s why I included some mentions of him in my short story “Connoisseurs of the Eccentric”. To quote:

At a young age, Kurt Gödel was called ‘Herr Warum’ (Mr Why) because of his insatiable curiosity. In June 1936, Moritz Schlick, chairman of the Vienna Circle, was assassinated by a pro-nazi student. This triggered a severe nervous crisis in Gödel, making him paranoid with an extreme fear of being poisoned. Gödel almost botched up his U.S. citizenship exam in 1947, when he was explaining that an inconsistency in the U.S. constitution could allow a Nazi-like regime1: Phillip Forman — the examinator — understood Gödel’s background, cut him off and moved the hearing to a routine conclusion. His fear of being poisoned was such that he only ate food that his wife, Adele, had tasted for him. When Adele was hospitalised in late 1977, she could not taste his food anymore, and Gödel refused to eat, eventually starving himself to death.

Gödel is also a towering figure in logic, philosophy and mathematics. His most lauded work are his two incompleteness theorems, which showed that David Hilbert’s program of finding a complete and consistent set of axioms for all mathematics is, in principle, impossible. So let’s get to the nitty-gritty:

A set of axioms is complete if, for any statement in the axioms’ language, that statement (or its negation2) is provable by the axioms. David Hilbert believed that it was just a mater of time to find such an axiomatisation for all of mathematics. Enter Kurt Gödel first incompletenesss theorem:

“Any consistent formal system F within which a certain amount of elementary arithmetic can be carried out is incomplete; i.e. there are statements of the language of F which can neither be proved nor disproved in F.”

Thus, you can have a formal system that is utterly consistent; i.e. ‘it just works’, yet there will be phenomena in that system that—while they function perfectly—cannot be proven. Gödel’s second incompleteness theorem expands on this by stating that the internal consistency of such a system is also not provable within the system (emphasis mine).

Therefore, if reality is a Gödel complete system; i.e. it follows a consistent system of logical statements—the laws of physics3—then there will be phenomena, especially phenomena that try to prove its internal consistency (such as the double-slit experiment, wich Richard Feynman stated as being’at the heart of quantum mechanics’), that are inherently unprovable. Note that this hinges on the assumption that reality is a Gödel complete system (of which more in the final part of this series of essays).

Therefore, I thought, it is through the interface between the double-slit experiment and Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems that we might be able to draw definitive conclusions about the falsifiability of the simulation hypothesis. And so we come to the thought-experiment I had before writing “David Bowie Eyes”:

Ted Kosmatka’s novelette “Divining Light” proposes that our failure to prove the double-slit experiment is the point where our simulation breaks;

However, if our reality is Gödel complete—that is, Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems apply to it—then by definition there will be phenomena that we are physically unable to prove. The double-slit experiment may be a prime example of those4, and is then a confirmation that:

Our reality is Gödel complete and:

Therefore the simulation hypothesis is wrong, because reality ‘breaks’ (is unable to prove certain penomena) where it is supposed to do so, meaning it’s real and not a simulation;

And that is what I thought, and I subsequently used this in the conclusion of my short story “David Bowie Eyes” (coming next Tuesday). My idea/planning was to have the story published by a fiction market, and then publish these essays here by way of explanation. However, after5 forty-two6 rejections7, an important paper was published;

This paper published in October last year proved that my conclusion is wrong, and that reality is basically Gödel incomplete. Does this mean that the simulation hypothesis is correct, after all? Read part 4—the final part—of this series to find out . . .

The mistake in my thinking was as follows: if reality is Gödel complete, then there will be phenomena—like the results of the double-slit experiment—that cannot be proven. That is correct. However, what I overlooked is that if reality is Gödel complete; that is, it arises from a set of consistent axioms, then—in theory—it can be simulated by a Turing machine.

Aaargh! (SF author bangs his head against the wall8.)

Of course, using the conclusions of the recent paper, I could have rewritten “David Bowie Eyes” to incorporate their findings. But that would have been dishonest to you, my readers, and myself9. So the concluding section still includes my wrongful thinking. When I’m wrong, I should own up to it10.

Finally, the big revelation is to come in the final piece of this series of four essays. . .

Support this writer:

Like this post!

Re-stack it using the ♻️ button below!

Share this post on Substack and other social media sites:

Join my mailing list:

Author’s note: basically11, Gödel’s Incompleteness theorems are meta12-statements of systems; that is, they try to look at a system from the outside. Prepare yourself, as things will get even more ‘meta’ in the final essay.

Until that, many thanks for reading!

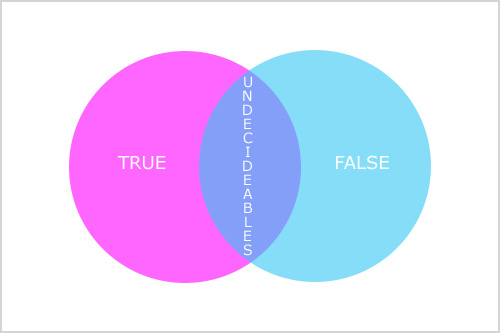

(Added later) When I downloading the top picture, I thought this was some AI contraption (which it probably is), yet it comes from an actual website: Gödel Space.

As many of you probably know, there is a thing called ‘Rule 34’: that is, if it exists, there is porn of it. I’m proposing a new rule for the AI age (number TBD13): if two completely unrelated words can be combined—say ‘Gödel’ and ‘space’—then there exists an AI-flogging website for it.

Jesus wept.

Yet I have to own up to my mistakes.

And this, unfortunately, has become acutely actual today;

An important distinction, see Karl Popper;

As stated in a formal Theory of Everything, which hasn’t arisen yet (a fact that should have given me pause);

The soon-to-be-revealed paper gives many other examples;

I’ve had a story accepted after forty-three rejections, so there’s still hope…;-)

My actual record is having a story accepted after 60 rejections. On the other hand, I had three pieces accepted at the first submission (out of a total of more than 90);

I’ve also had a story accepted three times in a row, and each and very time the market died before it could be published. It was cursed;

Without accompanying heavy metal;

Intellectual dishonesty gets you nowhere. Learning from your mistakes improves you;

And as I like to tell the students on our training courses (on the day job): “Don’t be afraid to make mistakes. The only people who make no mistakes are the ones who do nothing at all.”

A word I tend to overuse;

Not to be confused with that horrible company that runs facebook and other privacy digesting social media (and soon LLMs);

Maybe that should be an irrrational number like √2, π, φ, or e;

If you follow the logic to its ultimate conclusion, you sometimes forget what you were trying to disprove in the beginning.

The proofs of Gödel's Incompleteness Theorems go way over my head, too. There are fields in mathematics so esoteric, so crazy (at least to me, and my youngest nephew studies mathematics at the Universiity level, and he agrees) they make hallucinogetic drugs seem like the starting point, not the endpoint.

Yet I think the *implications* of Gödel's Incompleteness Theorems are clear. And next Wednesday I'll show that I failed to take the next step, which a number of well-established scientific researchers did. But I don't feel ashamed, but rather proud that I did get quite close.

Finally, I totally missed that ROOT is on your substack, so now I can check it out. You started a year before me. Respect!

Oh, actually I followed that perfectly well. I guess I don’t have trouble understanding the implications of Gödel’s theorems, just the proofs behind them. And I slapped my forehead there at the end.

Of course, if reality can be simulated by a Turing machine, then that’s good news for my own Substack novel, ROOT…