The Simulation Hypothesis, Reprise 1

Ockham's razor

This is the first essay in a series of four that might very well encompass the final word on this. Parallel to it, I will post a story called “David Bowie Eyes” that handles—amongst quite a few other things—this particular matter, cut into three sections, starting next Tuesday. Once that is out of the way (late next month), I hope to cover linked concepts such as intelligence and consciousness1. But first I wish to get the simulation hypothesis out of the way.

There are philosophers such as Nick Bostrom and David Chalmers who think there is a non-zero chance2 that we are living in a simulation. And Chalmers in particular—in his tome Reality+—states that it’s impossible to prove that we are not. This is commonly called the simulation hypothesis. Interestingly, late last year a paper was published that proclaims to have demonstrated that it is (im)possible3.

Until that paper, many people—me included—thought that the simulation hypothesis was highly to extremely implausible. For two main reasons:

The principle of parsimony (also called Ockham’s razor4): search for explanations constructed with the smallest possible sets of elements. Simplified as: the most straightforward explanation is most likely to be the correct one;

No justifiable reason: why would a highly advanced civilisation run such an intensely complex simulation? Just to study such stupid beings—especially from the PoV—as us? Couldn’t they employ all those resources for much more useful cases?

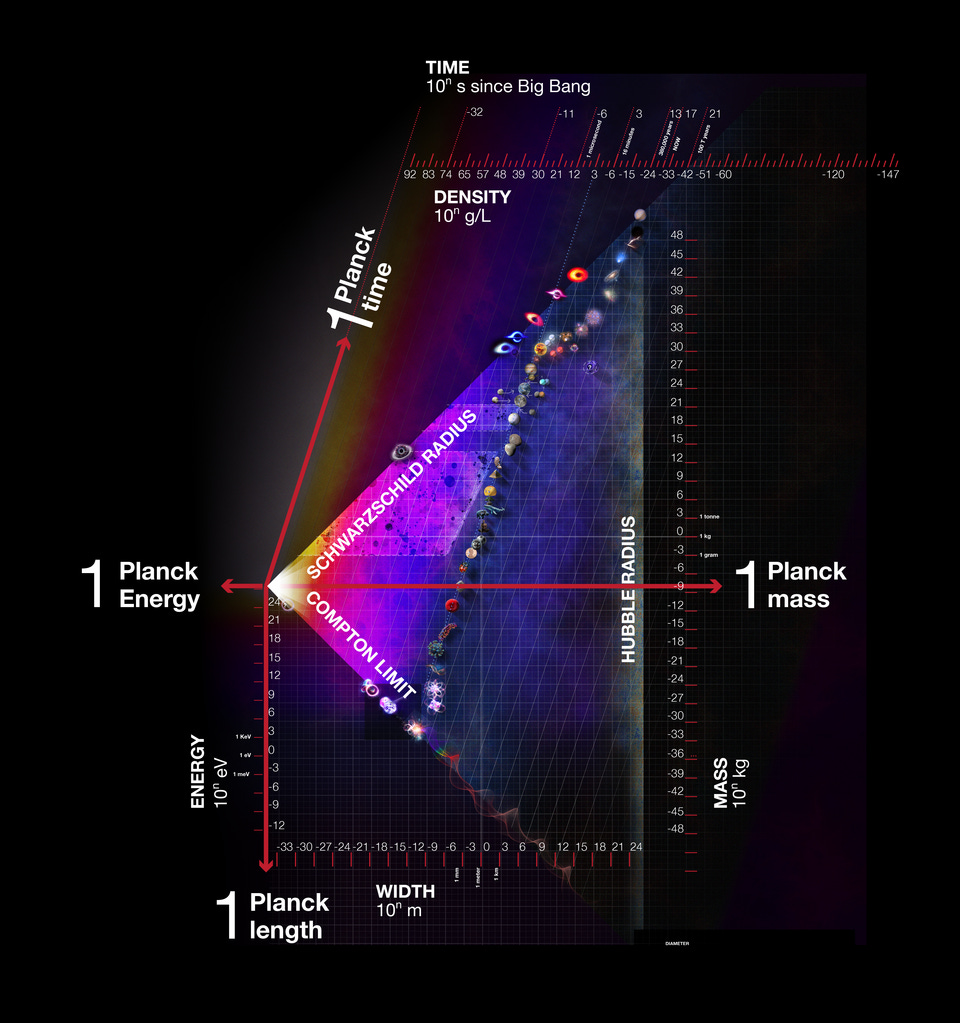

First and foremost: if our environment is a simulation, then it is an intensely complex one. Through scientific research we determined that the smallest parts of our reality that still make sense are Planck units, while we also have a good estimate of the size of the observable Universe.

FYI: the Planck length is 1.616 x 10-35 metres, while the estimated diameter of the observable Universe is some 93 billion light years or 8.8 x 1026 metres (where a metre is a unit of length that makes sense in our particular niche of reality). Roughly speaking, if we consider one Planck length a ‘bit’—or a ‘pixel’ in a Universe simulated through the holographic principle—then rendering the full universal simulation requires about 4/3 x π x r3 = 4/3 x π x (4.4 x 1026/1.616 x 10-35)3 = 2 x 10184 basic calculating units. Staggering doesn’t even come close to describing it. That’s a stupendous amount of data to simulate, in particular if all they wanted to simulate was humanity (according to the anthropic principle, which is about as far from Ockham’s razor as you can get).

So far, this means the simulation hypothesis is not strictly impossible—it just needs a Turing machine5 that’s many multitudes larger than the observable Universe with a complexity we can’t even begin to understand. We might as well call such a machine—or its programmers—gods. By now, William of Ockham is making turns in his grave.

And this doesn’t even consider the why. Why would such godlike entities perform such an inconcievably immense simulation? Just to study humans, who surely must be like ants, microbes, viruses of even less to them? It doesn’t make sense. Yet this means the simulation hypothesis is not strictly impossible, only intensely nonsensical6.

Despite all that, proponents of the simulation hypothesis in general and David Chalmers in particular still say: “Nanananana, you can’t disprove it!” Which is technically correct in the sense that it is theoretically possible to orchestrate a multitude of large masses in such a way that the resulting gravitational force would move, say, a pen on my desk one centimetre. But who would be foolish enough to consider, let alone attempt to perform it? Nevertheless, a philosophical standoff.

Of course, the simulation hypothesis is a welcome trope in science fiction. Prime examples include Stanislaw Lem’s character Professor Corcoran, Frederik Pohl’s The Tunnel under the World, and several novels by Greg Egan7 (there are many, many more). Of particular interest is Ted Kosmatka’s “Diving Light8”, originally published in the Asimov’s Science Fiction issue of August 2008.

In that novelette, Kosmatka forwards the idea that the double-slit experiment is basically the point at which the simulation breaks, thus proving that we live in a simulated environment. I thought that the idea was brilliant, yet the conclusion was wrong. Ironically, the recently published paper (I will reveal which it was in the final post), uses the same idea, but comes to yet another conclusion. Confused? To get to the finer points, we must first focus on the double-slit experiment.

Support this writer:

Like this post!

Re-stack it using the ♻️ button below!

Share this post on Substack and other social media sites:

Join my mailing list:

Author’s note: I know I posted about this before, but didn’t quite finish it. However, a recently published paper leaves me no choice. Therefore, in the next three weeks you’ll see my short story called “David Bowie Eyes” about it (cut in three parts) on Tuesdays, with the (more or less) accompanying essay diving deeper into the simulation hypothesis on the Wednesdays.

And yes, there will be a solid conclusion. Many thanks for reading!

Not in the least because it plays a major part in the current The Three Reflectors of Consensual Reality serialisation;

Bostrom puts it at about 33.33% if I understand him correctly;

I’m not saying which: for that you’ll have to read the follow-ups of this essay (evil writer…🧐);

I know, it’s predominantly spelled as ‘Occam’s razor’. How that happened is unclear, as it is originally attributed to William of Ockham—hence (IMHO) ‘Ockham’s razor’;

Or whatever you’d like to calll the computing device running the simulation;

So maybe the gods are doing it for the heck of it (which wouldn’t make them gods, but fallible beings just like us);

Most prominently in Permutation City, but also in Diaspora (“Wang’s Carpets”) and in Schild’s Ladder;

Which he expanded into a novel called “The Flicker Men”;

I don't want to spoil anything, even if my bias is clear. But something is going to be debunked.

I'm looking forward to the rest of this series. The convincing argument here against the simulation hypothesis reminds me of a similar debunking I did many, many years ago of some of the religious myths I grew up with (and which I will probably post to Substack someday): https://www.shunn.net/korihor/1997/08/im_special.html

Is "simulationism" just another flavor of faith? I'm eager to hear more.