The Hard Problem of Consciousness Refuted, Part 1

On the Origin of Qualia(*)

When the philosopher David J. Chalmers proposed1 the so-called ‘hard problem of consciousness’, he seemed to propose that some aspects of consciousness may never be understood. According to Wikipedia, the hard problem of consciousness is to explain why and how humans and others organisms have qualia, phenomenal consciousness, or subjective experiences. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy states it in more general terms as Why is it conscious?; that is, how to explain that certain functions, dyamics and structures2 feel subjective to a conscious entity.

In other words, we may eventually be able to explain—mechanistically—how consciousness works (the ‘easy problem of consciousness3’), but still not be able to explain why the things we experience feel subjective, or—more abstractly—‘why is the performance of these functions accompanied by experience4?’

So something is added to these functions—which in itself should be amenable to functional explanation—and that ‘something’ cannot be explained (some even say by definition).

This makes consciousness look like magic, something that is conjured out of thin air5. I disagree, as I think there is—at least one—functional mechanism that adds subjectivity to these functions inside our brain. Functions like observing colours, sounds and other so-called qualia, functions like the brain generating6 a prediction of what it will experience before the experience actually happens (see Being You by Anil Seth), and then reconfigure its prediction algorithms when the prediction is wrong, thereby constantly fine-tuning that particular mechanism.

This essay will focus on the origin of qualia. Follow-up essays will handle the conscious experience itself—why it feels subjective and why it is extremely unlikely that philosophical zombies7 could arise through evolution (and if they are possible, at all8).

I will limit this particular essay on the origin of colour qualia, in order to keep it within a reasonable length. I intend to demonstrate—via related research to which I’ll link—that the mechanism for colour qualia is very close to being understood and that it does not need consciousness to work9.

With regards to colour qualia, I think they are—in a way—supernatural (I prefer to call it ‘imaginary10’) because they only exist in our minds11. A little anecdote.

When I went to the Dutch Atheneum from the basisschool12, I wasn’t the ‘professor13’ anymore since very smart kids—quite a few smarter than me—from several counties were in my class, as would soon be clear. In the very first physics class, the teacher wanted to impress the idea that physics is complicated upon us. “For example,” he said, “do you know what colour is? Do you really know what colour is?”

This received a prompt answer: “Colour is the frequency of reflected sunlight,” one of my classmates said, adding: “Everybody knows that.” Well, I for one (at that moment) most certainly didn’t. It just goes to show that there are always smarter people than you.

I think that our physics teacher did not mean qualia, but exactly what my classmate answered (he most probably didn’t anticipate this level of smartassery). And the answer is physically correct.

It’s why spectrometers can measure frequencies both inside and outside of the so-called ‘visible spectrum’, where the visible spectrum is basically defined as the reflected frequencies the human mind has decided to transform to colours14.

It’s akin to how astrophycisists use computer programs to add ‘false colours’ to pictures of space from the James Webb telescope15. The utmost majority of the frequencies measured in these pictures are outside the visible spectrum, so do not have a ‘colour’ attached to them via the human brain. Yet the frequencies and amplitudes of this electromagnetic radiation are known, and eminently measurable. Then those frequency ranges are overwritten—in the picture—with a colour pixel combination that will produce visible colours to the human brain. I suspect qualia follow a similar process.

Basically, in our actual reality there is no such thing as a ‘colour’. There is electromagnetic radiation with a frequency and an amplitude. Amplitude translates to the energy content of a particular frequency—which we interpret as ‘brightness’ in the visible spectrum—while frequency translates as the number of cycles the electromagnetic wave completes per second—which we’ve learned to translate as a colour, but which, I suspect, was interpreted differently, originally.

Keep in mind that we rarely see a single frequency, but rather a range of frequencies. If we look directly into the sun—note, only do this during the totality phase of a total solar eclipse—we see all the visible frequencies at the same time (while ignoring those outside the visible range, whose nearest neighbours either heat us—infrared radiation—or burn our skin—ultraviolet radiation) and this combination is interpreted by our brains as ‘white’. If we see no light at all, the brain interprets that as ‘black’. The colours we experience are basically filtered frequencies; that is an object—fauna, buildings, clothes, posters, etcetera—that’s bathed in the unfiltered sunlight only reflects certain frequencies of it.

Via our optical system—the eyes and their lenses, the optical nerves that are connected to certain parts of the brain—we get a fairly good representation of the size, shape and various forms of the objects we observe. But the reflection of these objects also contain certain frequencies, and how does our brain represent these?

Remember, people already experienced colours before we invented mathematics. Had it been the other way around, possibly the very shade, the existential hue of an object might have been represented by a unique number capturing its frequency range16. But it doesn’t work like that.

So I suspect that way back in evolutionary terms, the neural predecessor of what eventually would become our brains mainly saw all these varied frequency ranges as variations between black—no frequencies—and white—all frequencies. Shades of grey. It’s what black-and-white pictures still do.

According to Ellen McHale, eyes started to develop in animals some 520 million years ago. Colours as qualia developed, most probably soon thereafter17. Because—here’s my speculation—to effectively discern between all those shades of grey18 one would need huge eyes, and these are vulnerable. A strike against developing a new survival trait. Yet being able to discern all those shades of grey does give survival advantages; namely being able to more easily recognise edible (or poisonous) food, notice predators, select mates, and other survival traits. Due to the speed of light being so much higher than the speed of sound19, let alone the relative slowness of smell and odour20, vision got the front seat in the development of new applications, because this immediately increases a species survivability.

Not only that, but as Ellen McHale says in “What is colour?”:

“Animals evolved to use colour to their advantage. They developed bright feathers and scales to attract mates and deter predators. They even developed ways to use colour so they could camouflage themselves and disappear into their surroundings.

In the plant world, plants evolved to have brightly coloured flowers to attract pollinators, like bees and butterflies.”

Therefore, there was—and is—a lot of evolutionary pressure to make the vision system more discernable; that is, both more acute and precise. Which means shades of grey just don’t cut it. Meaning at some point, some nervous system developed the qualia colour; that is, it added a marker that is only visible within that nervous system for a certain type of visible frequencies. Call those early markers red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet, if you will21.

Which is all nice and well, but what about the actual mechanism that produces the illusion of colour? Here are two papers that basically blew my mind:

Information and the Origin of Qualia by Roger Orpwood (April 21, 2017);

Structural Qualia: a Solution to the Hard Problem of Consciousness by Kristjan Loorits (March 18, 2014);

(Note that I’m putting the Orpwood on top because it is basically an extension and modification of his earlier paper “Qualia could arise from information processing in local cortical networks”, March 14, 2013, meaning Orpwood may have just been ahead of Loorits.)

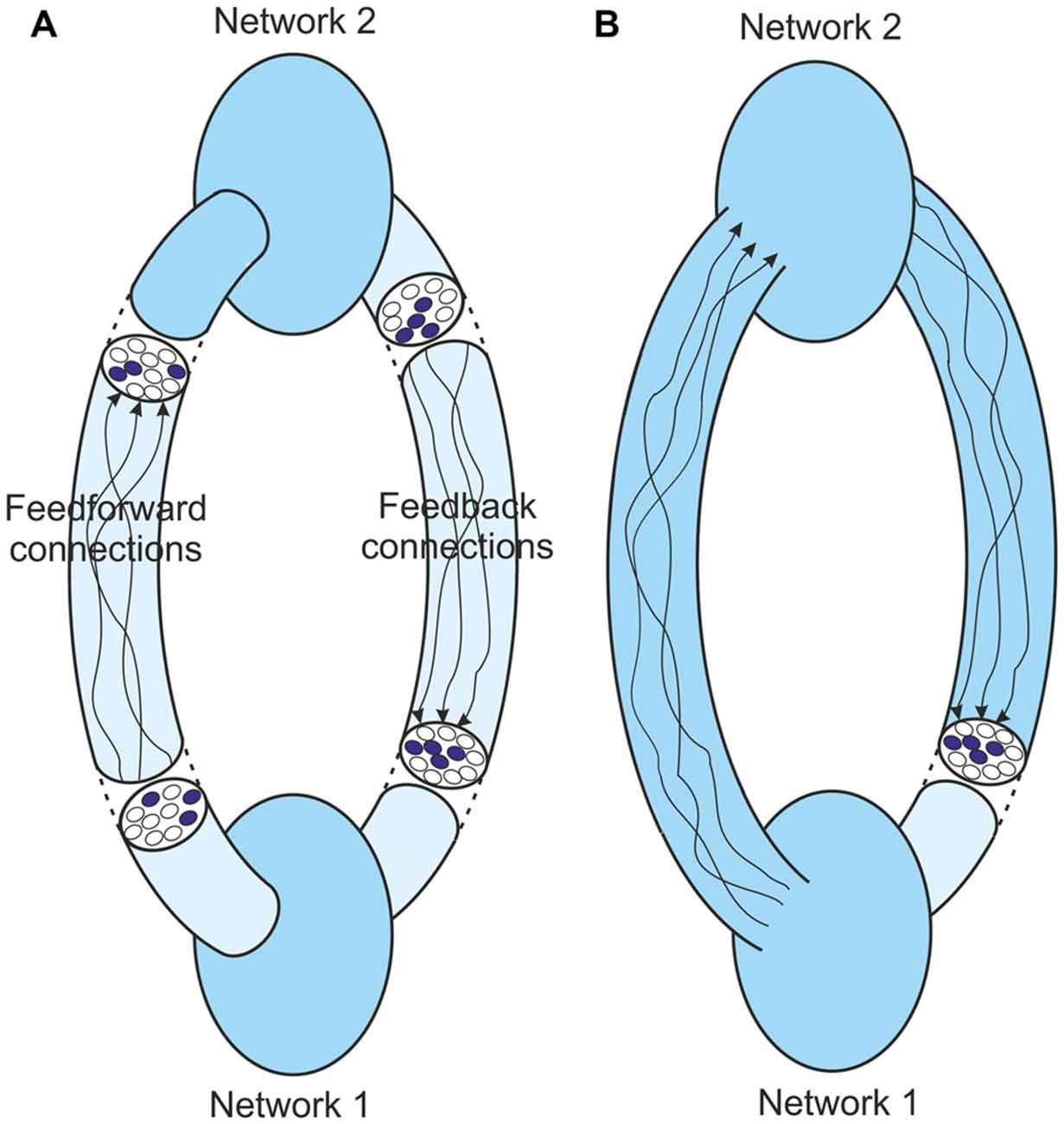

Personally, I prefer Roger Orpwood’s hypothesis of the way qualia are generated. It describes, step by step, how the actual mechanism—a resonant loop between two networks—inside the brain might work. Meaning that, if this process is correct, then it is something that will have been embedded in our DNA for many millions of years (because it is repeatable and it provides great survival benefits).

Basically, this is AR—Augmented Reality—avant la lettre. In order to enhance the differences in reflected frequencies, the enhancement—the colour quale—is something that only exists in our brains. It does not exist in physical reality. Yet because almost all people experience it in exactly the same manner—evolution at work—it feels real.

Kristjan Loorits’s approach—also discussed in George Musser’s Nautilus article “Is the Hard Problem Really So Hard?”—describing a ‘qualia space’ in which each quale is defined in relation to every other quale is—I strongly suspect—having it backwards, as first saddling your specimen up with massive synæsthesia and then gradually sorting it our until all sensory input is categorised in its fitting section does not seem a way that delivers new survival traits, rather the contrary. For what it’s worth, it makes much more sense to me that qualia (the mechanism that produces them being quite similar for various sensory inputs) came first, and that wrong connections in the brain—correct qualia-generating mechanism but connected to the wrong sensory input aka synæsthesia—came afterwards.

On top of that, I suspect blind people will recognise colours because this encoding of frequency-range-to-colour-quale is genetically embedded in the brain (so if one part of our vision system does not work, the qualia-generating mechanism might still work, but is not activated).

Make no mistake, both the Orpwood and the Loorits papers describe a process in which a physical input is converted into a subjective parameter in the brain. The objective made subjective. And this process is extremely consistent, as the utmost majority of us humans (animals experience different types of colours) experience colours the same22. No magic, no unexplainable things. Science.

This process of imaginary colour generation in the brain (or nervous systems of most animals) is so commonplace that evolution has adapted to it (see Ellen McHale quote above). So two things:

Even insects experience colour, meaning colour qualia do not need consciousness23;

While the colour experience feels subjective, it is highly consistent amongst humans, meaning this particular experience of ‘subjectivity’ is quite an ‘objective’ one24;

Two strikes against the hard problem of consciousness. On top of that—according to Orpwood’s paper—the qualia-generating mechanism works the same for smell, taste and other sensory inputs.

TLDR: qualia are generated through a mechanism that is independent from the mechanism that generates consciousness25.

Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the utmost majority of qualia developed as survival traits, not functions to mysteriously make consciousness ineffable. One down, two to go: the notion of philosophical zombies (which will need a series of essays) and phenomenal consciousness (which, I suspect, follows almost automatically through the evolution of agency). Stay tuned!

Author’s note: sorry about the radio silence. Things are sometimes so busy and demanding at the day job that I arrive home every evening too exhausted to produce quality writing. This may happen (silence for a week or two) in the coming months, but should decrease after May and—if all goes well—end after August. I’ll explain at that time. In the meantime, thans for your patience and thanks for reading!

(*): Paraprase of Darwin’s magnum opus is inentional;

Chalmers may not have been the first to come up with the problem, but he was the first to coin the name;

Things like—but not limited to—qualia, thoughts, and feelings;

Which, I strongly suspect, is actually harder;

Which is like a reverse Catch-22: if these functions did not generate experience we would not be conscious;

Or not even that;

See also Erik Hoel’s infamous tweet: “The main purpose of the brain is to generate a stream of consciousness” (Apil 5, 2021);

An important argument used in favour of the hard problem of consciousness. I’ll get back to those at length;

For which we need to go deeply into Peter Wats’s groundbreaking Blindsight and Echopraxia SF novels;

Note that this does not imply that we are non-conscious beings or that philosophical zombies are possible: those are different arguments that I will address in my follow-up essays;

Also a quality that seems to be powered by consciousness;

And probably in the minds of animals with vision;

Say, from primary to secondary education, where Atheneum and Gymnasium form the highest level of secondary eduction in The Netherlands;

My nickname for a while in the village where I was born;

Via a long and arduous evolutionary process;

The Hubble telescope is primarly optical while the James Webb telescope observes in the infrared specturm;

Like the colouring books I used as a child (and which are now also electronic);

The same is true for consciousness: it didn’t appear out of nowhere, but gradually developed over evolutionary times (probaby starting with agency—See Michael Tomasello’s The Evolution of Agency—and gradually becoming sentience, consciousness and self-consciousness);

And there are literally millions of them, see not only the ad copy of how your computer monitor is calibrated to ‘millions of colours’, but also the existence of people—mostly women, IIRC—who can actually discern millions of different colours;

In our atmosphere or ocean;

Which depend on the wind, which is fickle; that is, not always reliable;

Most likely—as with all evolutionary processes—a long, arduous and semi-random selection process took place that eventually led to the colour qualia we now, basically, imagine;

Some women are reported to be able to distinguish millions of colours: that’s the extreme end on one side. On the other side, we have colourblindness;

Or that insect are conscious, which I consider extremely unlikely. Sentient, yes. Fully conscious, no;

And it’s far from the only one;

Qualia are observed in consciousness, but do not need consciousness to be generated;