A caveat: I am doing research for a novel I intend to write which is set during the reign of King Nebuchadrezzar II of Babylon, some two hundred years after the events described in Babylonia. Which is why I read this novel with extra interest. Suffice to say I was richly rewarded.

Babylonia describes the rise of Semiramis—a common woman who eventually became Queen Sammuramat of Assyria. It’s described as ‘historical fiction’, which is apt, as part of it resonates with historical sources, while the rest is made up. The latter because a lot of what actually happened is lost in the ravages of time.

Admittedly, I’m reading this for selfish reasons, hoping to learn from it while I work on my next novel. For one, the events in the book—Assyria invading Media and conquering the city of Balkh, and Assyria waging war with Babylonia—provide insight on why, some two hundred years later, Babylonia under King Nabopalassar and Media under King Cyaxares would join forces and subsequently conquer and destory Nineveh and Assur, effectively ending the Assyrian empire. For another, it provides an intriguing glimpse of the roles of women in these times (which are, unsurprisingly, historically underreported).

Anyway, once governor Onnes—half-brother of King Ninus—decides to marry the common girl Semiramis (she’s barely a woman, yet many women were married very young in these times) who he meets in the remote city of Mari, and in whom he sees, if not a soulmate, at least a kindred spirit, the plot thickens when they move to Kalhu, the capital of Assyria, the seat of power.

As a perfect stranger, Semiramis must gradually find her footing in the morass of palace intrigues, the snake pit of royal (dis)loyalty. Nevertheless, the same court shenanigans set Ninus—King Shamsi-Adad—up for a military campaign against the city of Balkh, deep within the kingdom of Media.

Those sieges and battles were relentless in intent and absolutely brutal in their execution. The novel doesn’t flinch from portraying the gruesomeness of these fights, and even achieves extra depth through displaying both Oness’s and Semiramis’s intense PTSD after the battle at Balkh. These scenes are not for the faint of heart, yet essential in depicting the utter brutality of the Assyrian army, something they were—and wanted to be—renowned for1.

The scenes at the court of Kalhu are equally captivating in their display of behind-the-curtain intrigues and back-stabbing power games. Ultimately, not men like the ruthless Commander-in-Chief Ilu, the barbaric Prince Marduk, or the sly Spymaster Sasi, but Queen Mother Nisat becomes her most formidable opponent.

As the slave Ribat is introduced—his true role becoming clear at the very end—this also gives a sobering look at those at the very bottom of this society's ladder, plus an extra point of view in the court intrigues, as slaves are—to the nobility—part of the background and, as such, effectively invisible. Meaning slaves sometimes can’t help but be witness of surreptitious acts of betrayal.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is not only widely quoted and referred to in the story itself, it also reverberates in the love triangle of Onnes, Semiramis, and King Ninus (respectively representing Enkidu, the goddess Ishtar and Gilgamesh). It imbues this multi-layered novel with additional depth.

A few nitpicks:

(i): The title Babylonia is a misnomer as almost all the important action—with the exception of two military campaigns—takes place in Assyria. As such, Assyria would have represented the content better2.

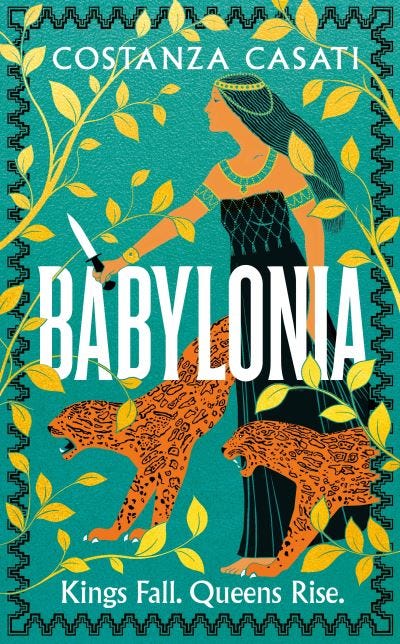

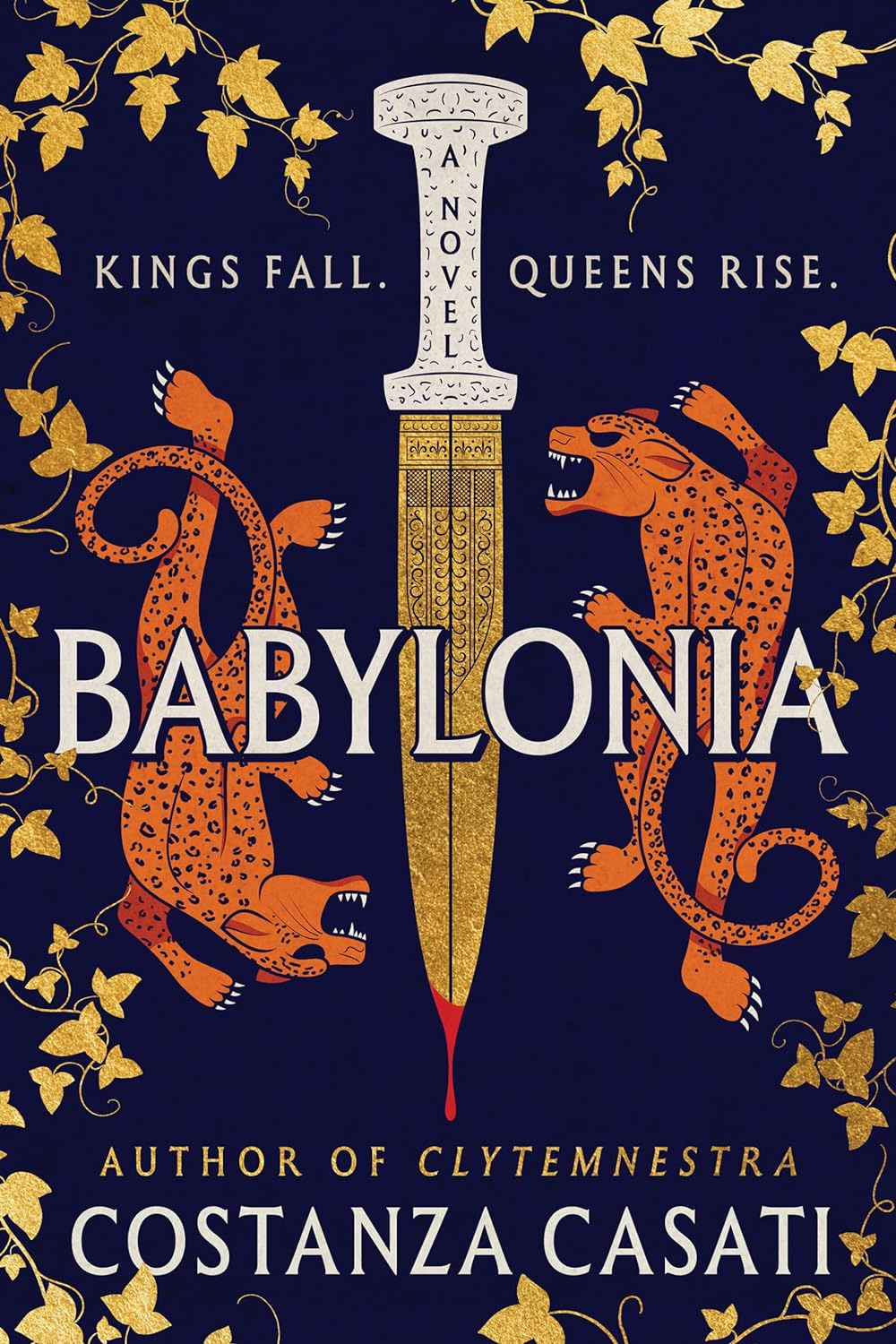

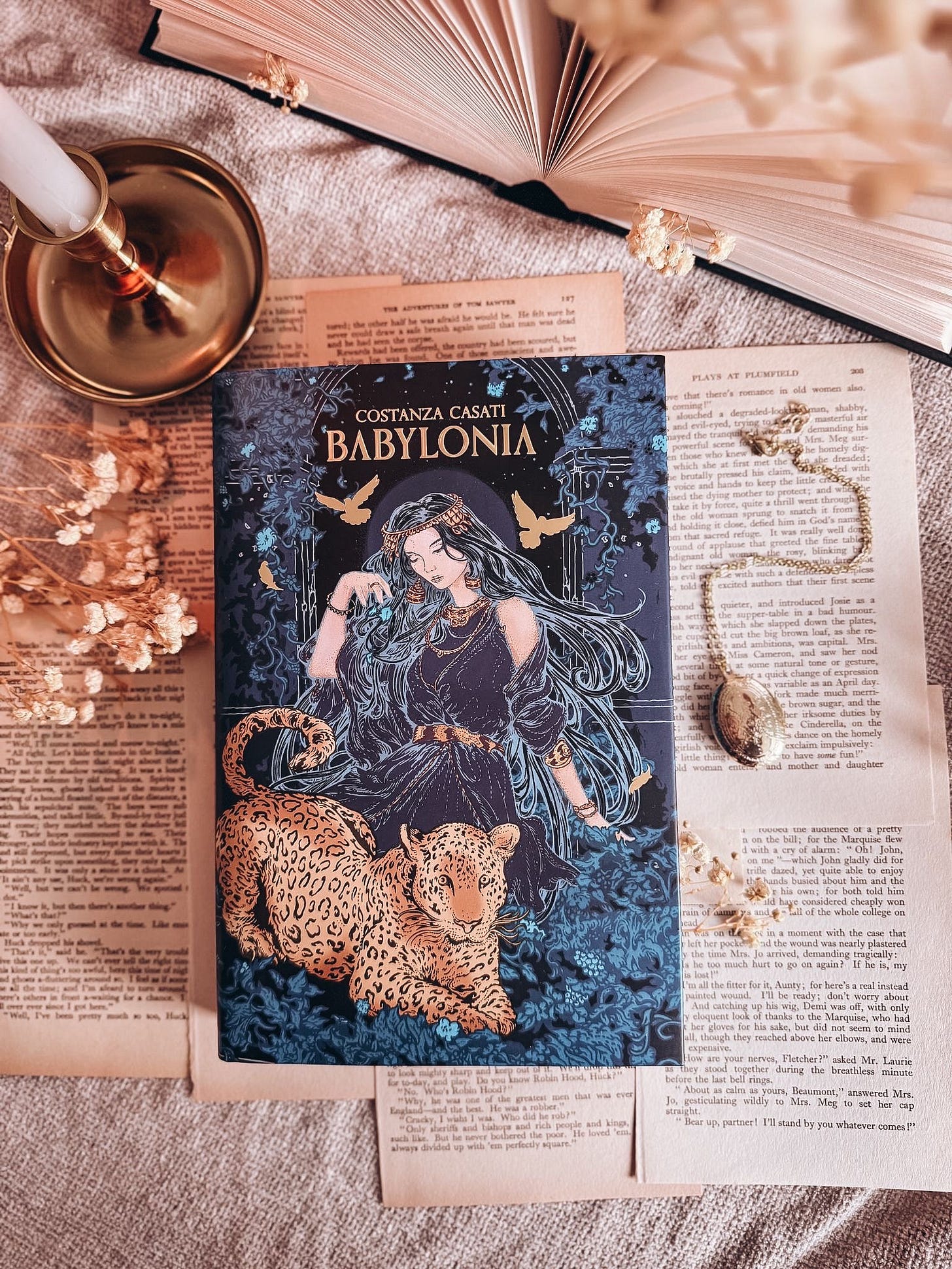

(ii): The Penguin cover—the predominantly green one, which was the one of my ebook—shows Semiramis with two leopards, while in the novel she has only one. There’s a predominatly blue cover with a yellow knife in the middle3 that also shows two leopards. And there’s a cover (also predominantly blue) that depicts Semiramis with one leopard4. Take your pick5.

(iii): The ending is a bit too neat6. Ribat the slave who was set free by Semiramis and who now is a scribe, is called in by Semiramis to join the court’s ritual healers and save the mortally wounded King Ninus after the battle with the armies of Prince Marduk. Semiramis knows how Ribat nursed her back to health on several occassions, and because she implictly trusts him she wants him to be there, nursing her husband back from the brink of death.

Nevertheless, Ribat also knows that Queen Mother Nisat was instrumental in killing his mother. So now Ribat repays her by withholding the willow bark extract that might have saved the life of her son. This, I think, is out of character.

Throughout the novel, Ribat has been depicted as a survivor who will do anything not to be caught or killed. If he feeds King Ninus the willow bark extract and the king survives, then Semiramis will forever be thankful to him, and protect him. About as safe as it gets in treacherous Assyria.

Now he risks Semiramis’s wrath if she finds out he didn’t feed Ninus the willow bark extract, which is a highly dangerous prospect. So would Ribat risk this just to get an indirect revenge on Nisat? I’d call that highly unlikely.

On top of that, according to Wikipedia, King Shamsi-Adad V (the Ninus character in the novel) probably died when his son was still young, so Semiramis became Queen Sammuramat—a queen regnant—until her son became old enough to be king, not—as in this novel—when she was still pregnant of him. This turn of events sounds more plausible to me than the (in)tense denouement of Babylonia, while I do appreciate the careful set-up to it.

Make no mistake, despite these nitpicks I recommend this novel highly. This is a compelling story of how a woman of common ancestry can rise to power in ancient, brutal times, deeply researched while using historic sources to the best of their availability. And it’s a testimony to the quality of Casati’s writing that she fills the historic gaps with such verve and plausibility. While we may never know what actually happened, this is—like the Epic of Gilgamesh—a story for the ages.

On top of that, the story ends at the very beginning of Semiramis’s reign. In the novel, she dreams of rebuilding Babylon. Wikipedia mentions that Queen Sammuramat was involved in a military campaign supporting the kingdom of Kummuh in which (to quote the inscription of the Pazarcik Stele):

I smashed Attar-šumkī, son of Abī-rāmi, of the city Arpad, together with eight kings, who were with him at the city Paqarḫubunu, their boundary and land.

Material enough for a sequel which I’d buy without a second thought.

Support this writer:

Like this post!

Re-stack it using the ♻️ button below!

Share this post on Substack and other social media sites:

Join my mailing list:

Author’s note: in between all the copy-editing, I do read and spend some time researching my next novel. This novel allowed me to combine both: win-win!

Now I’m wondering to what to read next, preferably a modern SF novel. Recommendations welcomed, and many thanks for reading!

Terrifyingly, the Medes were even more brutal two hundred years later when they—together with the Babylonian army—sacked first Assur, then Nineveh, Assyria’s new capital. Its inhabitants—including children—were slaughtered en masse and the entire city burned to the ground, including the religious temples. Supposedly it shocked the Babylonians, who lamented the sackings with sorrow and remorse;

Maybe Penguin’s merketing department throught ‘Babylonia’ would sell better than ‘Assyria’;

The Deluxe Hardcover Edition, if Barnes & Noble is anything to go by;

And I’ve also seen a version of the Penguin cover with a bue background;

As is the general set-up, because I don’t think history progresses in neat three-year periods;