Notorious examples of chatbots and AIs writing chatting online and/or articles (I’m not pretending that this list is complete, far from it. More on Wikipedia):

Microsoft’s AI chatbot Tay (which started spewing racist and hateful comments, and was shut down in less than 24 hours);

Scatterlab’s chatbot Lee-Luda (launched in South Korea) quickly became a foul-mouthed bigot, while it presumably was also fed personal user data (without anybody’s consent);

Google’s AI chatbot LaMDA claimed to be sentient;

Blenderbot 31 who claimed “the fact that I’m alive and conscious right now makes me human”;

Facebook’s Project M, touted as the company’s answer to Google’s AI assistant, Amazon’s Alexa and Apple’s Siri, initiated in 2015 and shut down in 2018, “after an underwhelming run”;

After all these—very public—failures, the arrival of chatGPT seemed like a breath of fresh air. ChatGPT, so far, isn’t openly racist, nor promotes hate speech. It doesn’t claim to be conscious or human and produces writing that is both grammatically correct, and mostly makes sense. One gets the impression that chatGPT is climbing out of bottom of the Uncanny Valley (where many of its predecessors got stuck). It’s doing so well that the CEO of the company that created it is already managing expectations: ‘people are begging to be disappointed and they will be’. On top of that, the competition (Google) is “freaking out about ChatGPT”, announcing not one, not two, but twenty2 AI products this year3.

As a writer, I’m glad to see that a writing-generating AI gets so much attention (it’ll write anything: fiction, non-fiction, poetry, song lyrics, code and whatever you prompt it to write). But shouldn’t I be afraid that it’ll eat my lunch? Answer at the end of this essay.

Before we get to ChatGPT and fiction writing, it must be pointed out that ChatGPT and other text-generating AIs are already widely used:

CNET uses AI tools both so extensively and surreptitiously, that their own editorial staff wonders: was this story written by AI or a co-worker? Even today, they’re still not sure;

The AI-generated articles seem to appear most often in CNET Money, and after some intense criticism (not just about the use of AI tools, but that these tools made big mistakes, as well), this disclaimer was added to the byline of these article: “This article was assisted by an AI engine and eviewed, fact-checked and editied by our editorial staff.”;

Students around the world (including The Netherlands) are using chatGPT for their homework and to cheat during exams:

One viewpoint: “How ChatGPT robs students of motivation to write and think for themselves,”4;

Different viewpoint: “ChatGPT: Students could use AI to cheat, but it’s a chance to rethink assessment altogether.”;

And the CNEt saga foes on: “CNET’s AI Journalist Appears to Have Committed Extensive Plagiarism” (it’s hard to keep up at the moment);

The reason that ChatGPT is becoming more widely used for articles is that it can mimick the tone and style of many, very bland, articles extremely well. So much so, actually, that fellow Substack writer Erik Hoel dubs it a boring bureaucrat, its products ‘the banality of AI’. I agree, it adds vague disclaimers, clichés and unfalsifiable abstractions. It never seems to take a firm position, as it always looks at both sides of the coin, to an absolute fault.

I tried to give it prompts that would force it to take a position, but to no avail:

Explain why the simulation hypothesis is true:

The simulation hypothesis proposes that our reality is actually a simulated reality, created by a highly advanced civilization or entity. The hypothesis is based on the idea that the computational abilities of advanced civilizations will eventually reach a point where they will be able to create simulations of entire universes, complete with fully functional and conscious beings.

There are several reasons why the simulation hypothesis may be true. Firstly, the vast computational power needed to create a simulated reality may be within the reach of advanced civilizations. As technology continues to advance, it is possible that civilizations will eventually be able to create simulations that are indistinguishable from reality.

Secondly, the universe itself may exhibit characteristics that are consistent with a simulated reality. For example, the universe appears to be governed by mathematical laws and patterns, which may suggest that it is the product of a highly ordered and structured process.

Additionally, some physicists have argued that the fundamental nature of reality is indeterminate and probabilistic, which is consistent with the idea that our reality is a simulation. The observer effect, in which the act of observing a phenomenon changes the outcome, may also be evidence of a simulated reality.

Overall, while the simulation hypothesis remains a controversial and unproven theory, there are some compelling reasons to believe that it may be true. Further research and experimentation will be needed to fully understand the nature of reality and determine whether or not we are living in a simulated world.

See how the last paragraph basically changes my prompt from ‘is true’ to ‘might be true’?

Describe the solution of the Fermi Paradox:

The Fermi Paradox is the apparent contradiction between the lack of evidence for the existence of intelligent extraterrestrial life and the high probability that such life should exist.

There are many possible explanations for this paradox, but one possible solution is that intelligent life is rare in the universe, or that the conditions necessary for the development of intelligent life are extremely difficult to come by. Another possibility is that intelligent civilizations may exist, but they are so far away from us that we have not yet been able to detect them. Alternatively, it is possible that intelligent life exists, but it has not yet developed the technology necessary to communicate with us. It is also possible that intelligent civilizations have existed in the past, but they have either gone extinct or have not yet reached our level of technological advancement.

Ultimately, the solution to the Fermi Paradox remains a mystery, and it is up to scientists and researchers to continue searching for answers.

I see a pattern to its answers: first it regurgitates what the topic actually is, then it gives ‘several reasons’, ‘many possible explanations’—it won’t be pinned down in a single position and then firmly defend it, as some humans can manage so beautifully—and ends with the conclusion that ‘more research is needed’ or that ‘scientists and researchers coninue searching for answers’.

This echoing of information it found in its huge amount of training data—mined from the internet up to 2021—without developing an actual opinion about a topic is—most probably—why several people called ChatGPT a ‘stochastic parrot’. I agree. It aggregates information from a stupendously large database (which, according to some, might eventually not even be enough),then generates text based on patterns it learned from its training data, meaning it can’t provide sophisticated responses and refuses to take a position in complex or abstract queries.

Therefore, it’s a nice tool for bland, boring and bureaucratic tasks, but utterly incapable of delivering truly creative responses. Which coincides with the general take so far, namely: “AI-generated art/writing/other skills remains in the early innings, so for now it’ll augment work rather than replace it”.

Evidently, AI tools are becoming de rigueur in many companies, for better or worse. But will they replace the profession dear to my heart; that is, the fiction writer? Let’s look into a few prompts I used to check this out:

Write a Halloween story in the style of Stephen King:

It was a dark and stormy Halloween night, and the town of Willow Creek was shrouded in a thick fog. The streets were empty and quiet, as the town's residents huddled inside their homes, afraid of the terrors that lurked outside.

But for one young couple, Halloween was a night of adventure and excitement. They had decided to explore the abandoned amusement park on the outskirts of town, despite the warnings of their friends and the eerie whispers of the townspeople.

As they wandered through the abandoned park, they felt a creeping sense of unease. The air was heavy with a sense of foreboding, and they could hear strange noises coming from the shadows.

But they pushed on, determined to uncover the secrets of the amusement park. They soon stumbled upon an old fortune teller's booth, and they decided to take a chance and enter.

Inside, they found an old woman, hunched over a crystal ball. She looked up at them with piercing eyes and a twisted smile, and began to speak in a raspy voice.

"You are in great danger," she said. "The park is haunted by the spirits of those who were killed here, long ago. They are looking for new victims, and you are next.”

The couple was terrified, but they refused to back down. They ran from the fortune teller's booth, desperately trying to find a way out of the park. But as they ran, they were pursued by the ghostly spirits, who seemed to be closing in on them from all sides.

In the end, they managed to escape the park, but they knew they had narrowly avoided a terrible fate. They vowed never to return to Willow Creek, and to never again underestimate the power of the supernatural.

Did anybody else cringe at the very first sentence? When the writer Nick Mamatas asked ChatGPT to write a story in style of Nick Mamatas, the first sentance was also “It was a dark and stormy night” (no link as this is only visible to Nick’s friends on Facebook), after which Nick concluded that writers didn’t have anything to fear from ChatGPT. I agree.

Describe the year of the cat in bizarro style:

In the year of the cat, the world was turned upside down. Cats were the dominant species, ruling over humanity with their feline whims and desires.

The streets were filled with cat-themed restaurants, cat-themed stores, and even cat-themed public transportation. Cats were worshiped as gods, and humans were treated as their loyal servants.

Every day was filled with cat-related celebrations and events. There were cat parades, cat fashion shows, and even cat-themed beauty pageants.

But despite the feline domination, some humans still clung to their old ways. They formed underground resistance groups, plotting to overthrow the cat overlords and reclaim their place at the top of the food chain.

However, their efforts were in vain. The cats were too powerful, too cunning, and too adorable. And so the humans were forced to submit to their feline overlords, living out their days as subservient pet-people in a world ruled by cats.

But even in their subjugation, the humans found some small measure of comfort. For in the year of the cat, they were surrounded by the warmth and purrs of their furry masters, and they knew that they were truly loved.

Points for trying, I suppose. But any real bizarro writer will just laugh at the sheer blandness in both content and execution.

Write a short story—not a poem—in which the fools have taken over the asylum in the style of Edgar Allan Poe:

The asylum was a place of misery and despair, a prison for the minds of the insane. But on one fateful night, a group of jesters, led by a charismatic figure known only as "The Fool", staged a coup and took control of the institution.

The staff were overwhelmed and overpowered, forced to flee for their lives as the jesters took charge. They declared themselves the new rulers, and began to impose their twisted sense of order on the inmates.

The once peaceful and medicated patients were now subjected to a never-ending carnival of madness. The jesters would parade through the halls, dressed in garish costumes, taunting and tormenting the inmates. They would force them to take part in twisted games and mock trials, all in the name of entertainment.

I, a curious traveler, happened upon the asylum during this time of chaos. I was immediately taken captive by the jesters and thrown into the madness. I was forced to participate in their twisted amusements, my mind and body pushed to the brink of breaking.

But even as my sanity slipped away, I knew that I had to find a way to escape. I bided my time, watching and waiting for my chance. And one night, as the jesters were distracted by their revelry, I made my move.

I fled into the darkness, my mind forever scarred by the horrors I had witnessed. As I looked back at the asylum, now a place of madness and despair, I couldn't help but think of Edgar Allan Poe and his tales of the macabre. For the fools had truly taken over, and there was no hope for the inmates trapped inside.

Poe’s actual story about this—“The System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether” was a satire (the title alone gives away as much). ChatGPT didn’t catch this, and is probably incapable of producing a satire at all, as it clearly doesn’t understand any original concepts, let alone knows how to satirize them.

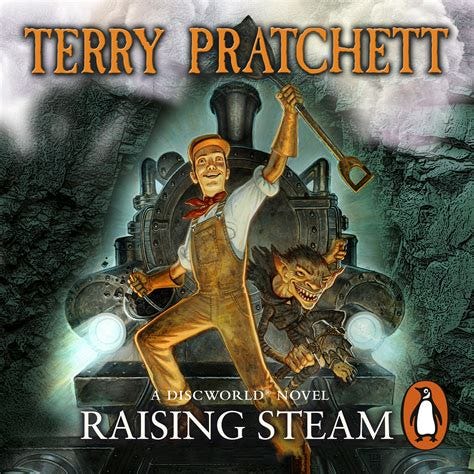

Write about how the Discworld discovers electricity in the style of Terry Pratchett:

In the magical world of Discworld, electricity was a strange and mysterious force that few understood. It was whispered about in hushed tones, rumored to be the source of great power and destruction.

But one day, a young wizard named Rincewind stumbled upon the secret of electricity. He had been experimenting with magic and alchemy, trying to find new ways to harness the power of the universe.

As he worked, he discovered a strange crystal that seemed to generate a powerful electrical charge. He quickly realized that this crystal could be used to create electricity, and he began to experiment with it, trying to understand its properties and uses.

Rincewind's experiments quickly caught the attention of the other wizards, who were eager to learn more about this mysterious new force. They began to work with Rincewind, studying the crystal and developing new ways to harness its power.

Eventually, the wizards were able to create a network of wires and generators, allowing them to distribute electricity throughout Discworld. The people were amazed by the new technology, and they quickly began to use it to power their homes, factories, and machines.

Electricity brought great changes to Discworld, transforming the way people lived and worked. It was a powerful force, one that could be used for both good and evil. But with the wisdom and guidance of the wizards, Discworld was able to harness the power of electricity, and to use it to create a brighter and more prosperous future.

This one’s a doozy; that is, a doozy of a black eye. It demonstrates that ChatGPT’s training set does involve (at least some of) Terry Pratchett’s Dicworld novels. However, Discworld fans know that about the very last person to understand the properties of something strange and new is Rincewind. In Unseen University that task would fall to Ponder Stibbons. And while Ponder Stibbons—pretty much against the wish of most of the wizards—might try to get this invention implemented outside Unseen University, the wizards are the very last people to help him with that. This would, most probably, be done by a character in the style of Moist von Lipwig, who would simultaneously be carefully controlled by the subtle yet ironclad machinations of Vetinari—the patrician of Ankh-Morpork.

Wisdom and guidance by the wizards? Any Discworld fan worth their salt will fall down laughing at the (absurdity of) the idea alone. Just to say that ChatGPT aggregates stuff from the Discworld novels without understanding anything about them, at all.

As mentioned in my previous essay—translatio, imitatio, aemulatio—one needs to understand the previous masters before imitating, let alone surpassing them. ChatGPT understands nothing, not even the bare essentials of narrative. This version—who knows what the future will bring, though—will never write original, exciting fiction.

Now why is that?

My best guess is that ChatGPT is missing humanity’s innate aptitude for narrative. The sensitivity for story is deeply embedded in the human psyche, and I strongly suspect it’s evolutionary ingrained. For example, check out THE EVOLUTION OF THE SENSITIVE SOUL by Simona Ginsburg and Eva Jablonka, which asserts that a complex form of associative learning—unlimited associative learning or UAL—to be the driving force in the evolutionary transition to basic consciousness. To quote:

UAL enables an organism to ascribe motivational value to a novel, compound, non-reflex-inducing stimulus or action, and use it as the basis for future learning.

In other words, organisms learn to incorporate new stimuli (or actions) by embedding them in a narrative, a narrative they can use for future interactions with the unknown. Here’s the origin of story, all the way back into deep evolutionary time. It’s in our genes, and—as far as a I know—AIs don’t have genes.

TL;DR: our innate talent for story developed over many millions of years.

Today’s AI-fiction-generating tools don’t have it. In other words: “It’s the narrative, stupid.” and neural networks don’t understand how narrative works. Without at least a basic understanding of what story is, AI-writing tools like ChatGPT will merely produce—see Tom Gauld’s highly apt cartoon—derivative drivel at worst or grammatically correct, empty clichés at best.

Again—as in the case of AI-art-generating tools (see my previous essay, part 1 in this series)—neural networks miss a quality that humans (and many animals) have acquired over evolutionary timescales. To the very best of my knowledge, there is no code or algorithm that can program the concept of narrative into an AI (otherwise, it would already have been done). Even though I suspect it’s embedded in our evolutionary code—the DNA of our genes—I also suspect that the expression ofthe genes (the body and the brain) is also essential to this. So I think it’s going to be extraordinary difficult to program an AI for storytelling, if not impossible.

So while—as a fiction writer—I’m not afraid of chatGPT’s current skills, there are other areas where I’m getting rather anxious. For one, chatGPT recently passed all three parts of the US Medical Licensing Examination. Do you wish to be diagnosed by a human doctor, or by an AI? On the other hand, people—me included—often use Google to find information about the condition they’re suffering. Often out of curiosity, or to have a second opinion, and—unfortunately—many because they cannot afford to go to a doctor. Neveertheless, I’d rather prefer a human doctor examining me that relying solely on internet or chatbot advice.

As such, it’s not the AIs themselves who are the real threat, but the lazy humans looking for shortcuts and the content-producing websites (and companies) trying to cut cost above all else.

Also, humans have used computers—and all the advanced products they created—for many decades now, and there are many examples where computers complement human skills very well. Note the word ‘complement’. As long as AI does not have truly human qualities—as outlined above—it will never really replace us in tasks that require true creativity, originality and agency. It might be very apt at other things do, of which more in the third and final part of this series of essays.

Bonus:

“Squawk! Randomness is the key to life, my feathered friends. You never know what tomorrow may bring. Embrace the uncertainty and let fate guide you on your journey. Repeat after me: ‘Life is a gamble, roll the dice and fly with the winds of change.’ Squawk!”

(Prompt: Generate a piece of derivative drivel from the point of view of a stochastic parrot.)

US-only at the moment;

I vaguely recall similar arguments when electronic calculators became popular;

It's greeat to read someone taking a more balanced (and thorough) viewpoint than many commentators, who just plug the hype even if it's detrimental to several human parts of the publishing pipeline. Another good breakdown of the massive caveat(s) which should be applied when using tools like ChatGPT can be found here:

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/dr-jeffrey-funk-a979435_ai-chatbots-learned-to-write-before-they-activity-7023240918396784640-KMad