The Replicant, the Mole & the Impostor

Part 2—the conclusion—of a duology where a reality event held in a refugee camp on a Greek island unfolds in an utterly unexpected manner. There will be 50 parts. Chapter 9: April.

—At the Lab—

“Alright,” Manfred Kafka says, “now we can set the record straight. Let’s go and show the world that we know what the Hell we’re doing.”

“You seem very eager,” Jennie Richards says. “While I’m as unhappy with the foul play as anybody else, this is not the first controversy to hit science.”

“After all,” Rachel Mónica Díaz says, “it’s done by humans. So—in order to prevent further controversy—we should hand science over to the replicant?”

“That’s already happening,” Léa Truchon says, “considering all the supercomputers and neural networks we use. As AI becomes self-conscious, let’s hope it becomes a collaboration.”

“You think the replicant is not self-conscious?” Themba Letesha says. “If it looks like a duck, walks like a duck, and quacks like a duck...”

“I think that’s one of the major questions coming right after this reality event is over,” Manfred says, “and actually the one who could have given the best answer—if the replicant is run like, say, a Chinese Cloud version of John Searle’s Chinese Room thought experiment—has left the building.”

“Has been marched out of the building,” Léa says. “So any last thoughts before we vote?”

“For my sake, as my specialty is the farthest away from the so-called humanities,” Themba says, “can someone give a short summary of the pros and cons of each of the three remaining candidates?”

“I’ll give it a shot,” Manfred says, while eyeing Jennie, Léa and Rachel Mónica. “Do feel free to correct me, of course. Here goes: Dewi Kamadjojo could be the replicant because she’s just too good as a teacher. She never loses patience, is never disappointed, never becomes angry; Shows almost none of the usual cognitive biases that normal humans have; Performs monotonous tasks without getting bored; Does not actively propose new ideas, only refines those that are mentioned; Her quick fling with Agnetha was a desperate distraction.

“She could be human because there are a rare few humans with an almost limitless amount of patience, such as Mother Teresa; She might be the rare human being that has actively overcome her cognitive biases; Her blushes are almost convincing.

“Omar Assisi could be the replicant because he remains sharp and active even after several nights of almost no sleep; He remembers everything, every little detail, as in there seems to be no difference between short- and long-term memory—which in humans gets sorted out during sleep; Shows none of the memory biases; Does not actively propose new ideas, only executes those that are implemented; Like Dewi, he has no real friends inside the group (an affair doesn’t count).

“He could be human because there are humans who only needs a few hours sleep per day;

There are humans with an eidetic memory (aka perfect recall); His flirting is about as mistimed and inappropriate as that of the majority of desperate males.

“Agnetha Lyngstadt could be the replicant because her virtual and AR skills are well-nigh indistinguishable from magic (no human could do that); She shows severe withdrawal symptoms when cut off from the internet; Her extravagant behavior is a major distraction.

“She could be human because there are nerds out there that match and surpass her skills in VR and AR; She’s one of many humans who are overdependent on the World Wide Web; There are lesbians out there who are both wilder and more iconoclastic, even if Agnetha would be loath to admit it.”

“To get to the heart of the matter,” Themba says, “you’re basically eliminating Agnetha because she shows all the hallmarks of a supernerd.”

“More or less correct,” Manfred says.

“But wouldn’t that be the perfect disguise?” Themba says.

“It would be if a supernerd is all she was,” Manfred says, “but there’s more to her. An extravagant lesbian who knows exactly how her scene works, a fierce fighter for equality who knows how it feels to be discriminated against, a feel for music that no computer program has been able to duplicate—just see the songs of the first virtual Eurovision Song Contest, which Dutch VPRO held when the real contest was delayed due to COVID-19: the computer-made songs were shite, all of them—and a set of cognitive biases that are an almost exact fit to her deepest convictions.”

“Still, a huge amount of people think otherwise,” Themba says. “They think she’s strange, to say the least.”

“A huge amount of people also voted for total idiots like Trump, Johnson, and Bolsanaro,” Manfred says. “I think the wisdom of the crowd is overrated.”

“So you don’t like the moodscapes that the refugees have developed?” Jennie says. “I really think they’re onto something with that.”

“I suppose those moodscapes can be a good tool to show where anybody’s gaps in education, experience, and empathy are,” Manfred says, “and should then try to motivate people to fill those gaps. Until it does, I’ll keep a ‘watch and see’ attitude.”

“In any case,” Themba says, “you think either Omar or Dewi is our replicant.”

“Yes,” Manfred says. “I’ve been thinking that for several months.”

“I agree,” Léa says. “I only think Omar is the most likely candidate, while Manfred thinks it’s Dewi.”

“Thirded,” Jennie says. “A Eurovision fan cannot be a replicant.”

“That’s not very scientific,” Rachel Mónica says. “Although I love Eurovision, too.”

“Those who know cannot explain,” Jennie says, “and those who don’t cannot understand.”

“Oh well. Any more questions?” Manfred says. “I suppose that—after all these months—our minds are made up.”

“Not mine,” Themba says, “but I’m always happy to consider new arguments.”

“I basically agree with Manfred and Léa’s estimates,” Jennie says, “and I do have my own main suspect.”

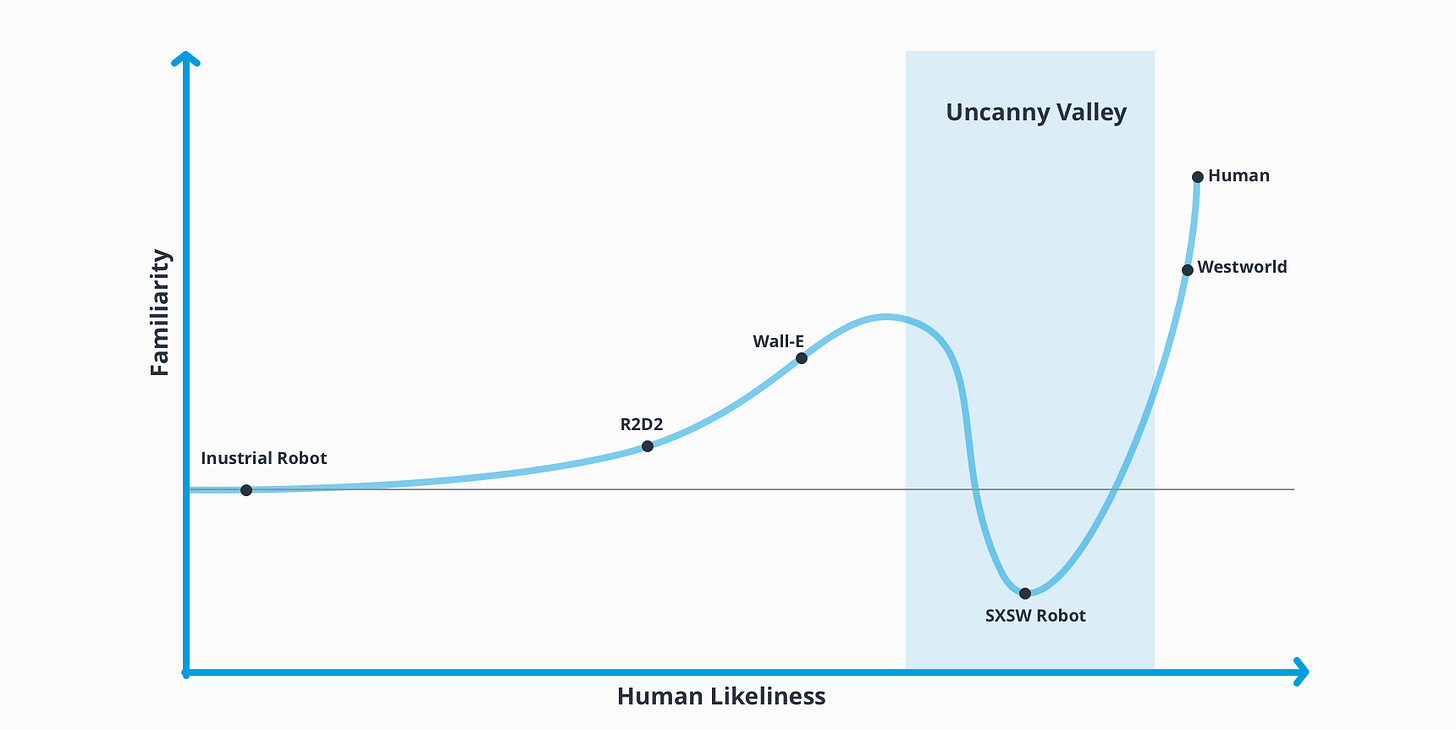

“I don’t disagree, either,” Rachel Mónica says. “Although I am both surprised and dismayed at how difficult it is. Either Dewi or Omar could function in our society without anybody ever suspecting they’re not human. As far as I can see, AI has crossed the uncanny valley.”

“That’s another major item to be addressed after this show is done,” Manfred says. “I suspect all of us to be overwhelmed with event invitations to discuss this.”

“Which is for later,” Léa says. “Let’s do it, then?”

“Yes. Write down your votes,” Jennie says, “so we can tab them.”

The five scientists take a blank piece of paper and write down their choices:

Manfred Kafka:

1. Dewi Kamadjojo

2. Omar Assisi

3. Agnetha Lyngstadt

Léa Truchon:

1. Omar Assisi

2. Dewi Kamadjojo

3. Agnetha Lyngstadt

Jennie Richards:

1. Agnetha Lyngstadt

2. Omar Assisi

3. Dewi Kamadjojo

Themba Letesha:

1. Agnetha Lyngstadt

2. Dewi Kamadjojo

3. Omar Assisi

Rachel Mónica Díaz:

1. Agnetha Lyngstadt

2. Dewi Kamadjojo

3. Omar Assisi

Total tab:

1. Agnetha Lyngstadt (11 points)

2. Dewi Kamadjojo (10 points)

3. Omar Assisi (9 points)

After the tabulation, Manfred and Léa maintain a shocked silence.

“Excellent work, the way you two unmasked Kobayashi,” Jennie Richards says, “and similarly, excellent work in narrowing the possible replicant candidates to two.”

“So why didn’t you—and others—vote for them?” Manfred says, “after all, our reputations are at stake.”

“True,” Jennie says, “but you might be overlooking the greater stakes. The bigger picture, as it emerges.”

“Aren’t we supposed to unmask the replicant?” Manfred says. “And show the world that we—at least—can still determine the difference between a human being and an artificial intelligence?”

“We can always show that proof afterwards,” Jennie says, “because right now, the reality event candidates—including the replicant—are initiating many fantastic and highly benevolent initiatives.”

“That happened more by accident than by design, right?” Manfred says. “Not to denigrate them—I fully support all the good they’re doing—but there certainly was, or is, no master plan behind it. It just happened.”

“In the end, it doesn’t really matter how it happened, but that it happened,” Jennie says, “and subsequently, that it keeps happening for as long as possible. And if we reveal the replicant before May 31. . .” Jennie leaves a deliberate pause.

“Then we shorten the period where all the really good things happen,” Manfred says, exasperated that he failed to see the true elephant in the room, “for everybody to see.”

“Indeed, the longer it remains completely in the eyes of the world,” Jennie says, “the longer a good example is set, and lived, the greater the chances that it will be copied.”

“I’m very sorry,” Manfred says, “but I hadn’t thought of it like that.”

“You won’t be the first scientist that got lost in the details,” Jennie says, “and certainly not the last.”

“And that’s why you have colleagues like us,” Rachel Mónica says. “Science today—more than ever—is strength in numbers and diversity of viewpoints.”

“So we’re intentionally going to vote for the wrong candidate,” Léa says. “So we unmasked Kobayashi for nothing?”

“It’s for the greater good,” Rachel Mónica says. “Consider it a little white lie for the betterment of humanity.”

“And your sleuthing was top class,” Jennie says, “but I—and Rachel Mónica and Themba, as well, I think—didn’t suspect Kobayashi was manipulating the vote because we were already voting that way.”

“You didn’t care about the bad guy because his actions—even if unintentionally—were good,” Manfred says.

“More like we didn’t bother checking if he was a bad guy,” Rachel Mónica says, “because we assumed his motives were the same as ours.”

“Nevertheless, even in this case a double negative doesn’t make a positive,” Themba says. “Kobayashi deliberately hid his previous—or actually not-so-previous—involvement with Electrified Quantum Sentient from us, even if he did or did not manipulate our votes. I’m glad we got rid of him.”

“And now I must vote with my heart,” Manfred says, “rather than with my mind?”

“That’s a false dichotomy,” Rachel Mónica says, “especially when your mind finally sees the bigger picture.”

“The sanctity of science,” Themba says, “superseded by the destiny of humanity.”

“Even if only temporarily,” Jennie says. “We can publish our true behind-the-scenes story after May 31.”

“Even if they’ll accuse us of being manipulated by VanderPol Excel,” Manfred says, “into keeping the show running for its maximum amount of slots?”

“Even then, it’ll be worth it,” Léa says, coming around to the other’s viewpoint, “if it has helped save only one life.”

“It’ll be hard—maybe impossible—to quantify,” Jennie says, “but I’m convinced it’ll be much more than one.”

“I see, and I apologize,” Manfred says. “This whole thing has been one giant roller coaster ride. Still, next month am I allowed to vote for the one I suspect most?”

“By then, it won’t matter anymore,” Jennie says. “The show ends May 31, irrespective if we unmask the replicant or not.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Divergent Panorama to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.