Doom Bells

through the noise it takes a while to see-ee eeh-he

doom bells are ringing for both you and me-ee eeh-he

She never thought she’d regret leaving a layer, but there she is. Two more layers—at least, if the spacing between them remains approximately the same—to go before they hit the Core, with unknown dangers—and opportunities—ahead, but still she wishes they—the Moiety Alien has become a faithful companion—could have stayed a bit longer. In any case, she’s replenished her stocks as much as possible and is as ready to enter the next stage as ever.

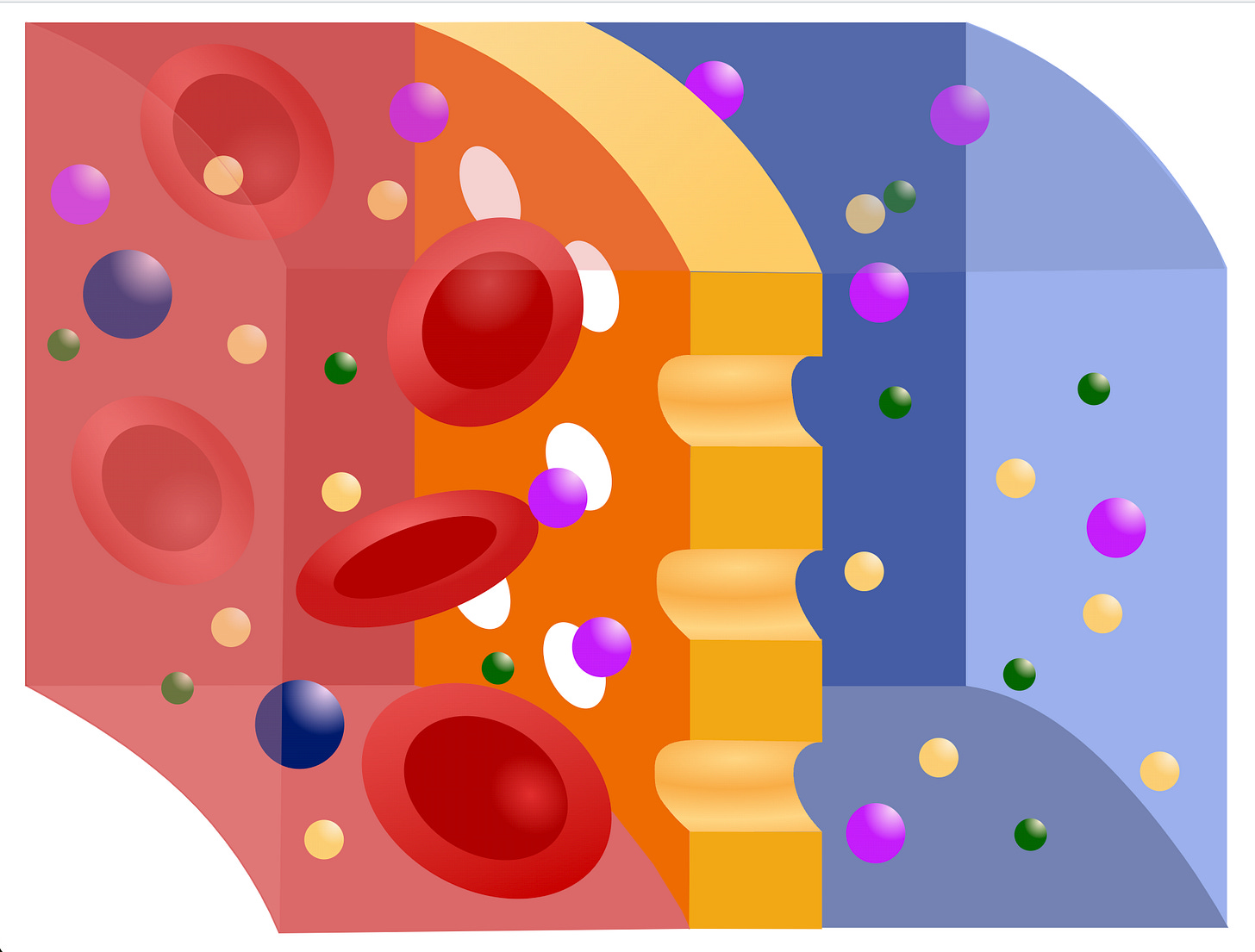

First, she must explore the next layer with a couple of probes, to see how perilous—or safe—it is, and, if necessary, to make preparations. While she sends five of her Kittis through the semi-permeable membrane, the Moiety Alien approaches it as well, four of its orbitals pointing to the Diaphragm Gate. Then the orbitals right in front of the gate shrink to near-nothingness as the other four double in size. It’s almost impossible to see, but Na-Yeli gets the very strong impression that the Moiety Alien ‘dips’ its minimized orbitals through the diaphragm. Then its biggest orbitals shrink, very quickly, and get back to their maximum size just as quickly.

The Moiety Alien jumps back as if it’s experienced something scary, painful, or both. Interesting, Na-Yeli thinks, is that how it knew that it couldn’t go through the gate at the bottom of the sea in layer three?

In the meantime, after their allotted ten minutes have expired, all of her five Kittis come back, but not quite in one piece. Their semi-sentience could best be described as dazed and confused, and while most of their instruments still function fine, a few have been ruptured.

The atmosphere on the other side is almost Earth-normal, with 89% N2, 10% O2, and several traces of noble gases. An unusually high amount of metal particles—in particular Cu, Ni, Al, and Si—while the pressure, when they were still able to measure it, is 1.03 bar and the temperature is a sweltering 313 ºK—hot, but nothing her cooling system can’t handle. Which wouldn’t seem so bad, were it not for the fact that all the probe’s microphones and sensitive pressure transmitters have been utterly destroyed.

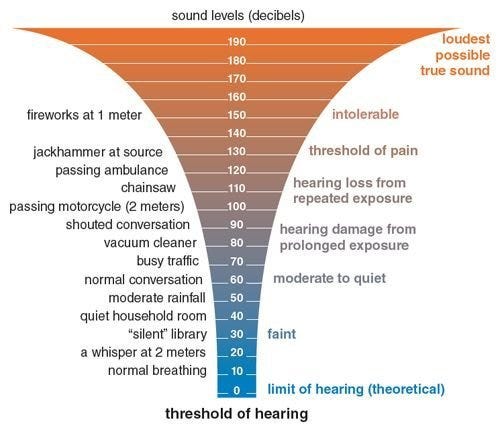

Before they gave up the ghost, the probes’ microphones measured excessive sound pressures in the frequency range of 300 to 4600 Hz. Sound pressures upwards of 180 decibels. Which doesn’t sound that extreme until Na-Yeli finds, through a quick database check, that decibel follows a logarithmic scale. In other words, 100dB is loud—the sound of a jackhammer like the one they had to use to get through the ice at the Berserker Forest’s North Pole—130 dB—the pain threshold of human hearing—is one thousand times as loud, and 180 decibel is one hundred thousand times as loud as that. It’s a sound pressure almost beyond belief, very close to—she checks her database again—the maximum possible sound pressure in air with a pressure of one bar, which is 194 dB. If the sound pressure gets any higher the fluctuations in air pressure it creates become so large that the low-pressure region hits zero pressure—a vacuum—and it’s physically impossible to go lower than that.

In any case, these are sound levels that will not just rupture her eardrums but will wreak havoc with her internal organs, as well. And she doesn’t want to contemplate what they would do to the orbitals of her friend, the Moiety Alien. They can’t go in there unprepared, they have to take some kind of precaution. Make that several kinds of precautions.

Na-Yeli thanks the fates that they have been able to carry a surplus of materials from the Berserker Forest—where they eventually were treated like gods—and sets out protective measures. For one, the excessively loud sound can be dampened, but the sound levels they seem to be up against are so extreme that they would need some twenty meters or so of sound-isolating material, which they don’t have, let alone will be able to transport through the Diaphragm Gate.

Sound can be canceled out by anti-sound, which is the same sound but with the opposite phase. There are two problems—OK, let’s call them challenges—with that. First, she needs to know the frequencies that carry the dangerous sound levels. For that, she can send scouting probes—carefully insulated, and with extremely sturdy microphones—in front of them, to measure the exact sound before it hits them. Better make a huge amount of these, Na-Yeli thinks, as they can be the sacrificial fodder that saves our asses.

Second, to fully cancel the amplitude of the dangerous sound, they need to transmit an equal amplitude at the opposite phase. 180 decibels—or even the theoretical limit of 194 decibels, let’s assume the worst—contains a tremendous amount of energy. To fully cancel that, her anti-speakers need to be huge and stupendously powerful. While she could conceivably prepare a pair of such ultraspeakers, she simply doesn’t have enough energy to keep them going throughout the half-round trip to the next Diaphragm Gate.

It’s not the pressure difference of the 194 dB sound waves that’s the problem: these are merely about 2 bar (from zero bar at the bottom end to 2 bar at the top end). No, it’s the energy they carry: at 194 dB that’s more than 10 MegaWatt per square meter. She needs to dampen that with the same amount of energy to make the resulting sound waves bearable.

But where does she get the energy from? She needs a pocket-sized nuclear reactor to generate this amount of energy, and she simply doesn’t have it. But then she remembers her early judo lessons: “use the force of your opponent against him.” Yes, it’s as if KillBitch and LateralSys are giving her hints at the same time.

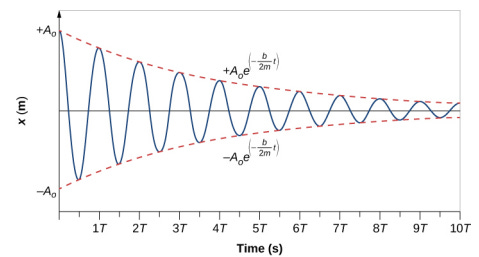

She must absorb the power of the incoming sound waves and then immediately send it back to them transformed as anti-sound. While the principle is sound (pun unintended), she must keep a dynamic balance, walk a dancing tightrope; that is, if she makes the canceling out too effective, she will not receive enough incoming energy for the next upcoming blast of noise. If she makes the canceling not effective enough, the leaked sounds will kill or severely hurt her and her friends.

This may tax my onboard computer to the max, Na-Yeli thinks, only one way to find out. So there she is, designing—with all the engineering data of humanity’s history backed up in her triple-redundant quantum computers to help her—a type of metamaterial that not only can reflect tremendous amounts of energy but at exactly the right frequencies, as well.

Luckily, predecessors of it have been made in huge quantities, often at high-quality levels. They were called loudspeakers. And what Na-Yeli is producing is derived from the good old electrostatic loudspeaker (ESL), with the biggest difference being the power source.

While this energy-absorption-and-reflecting-energy-back will never be 100% efficient, that’s fine, as she intends to use the surplus energy for propulsion (judo trick part two).

The membrane of metamaterials she’s designing must both constantly absorb the energy aimed at her and reflect it as anti-sound. That’s her next problem—they never seem to end—as she can’t do both at the same time. And letting one membrane absorb while another reflects also doesn’t work because they’re in each other’s way.

Well, what about the principle of Alternating Current, Na-Yeli thinks, applied to this crazy acoustic set-up. Assuming 50 Hertz, that would be 20 milliseconds of absorption alternated with 20 milliseconds of reflection. And she can increase or decrease the frequency to see what works best. But that would still leak a lot of the incoming power. Thus, below membrane 1 we have membrane 2: reflecting the leaking power at itself using the same principle. Followed by membrane 3, etcetera. Membranes all the way down? No, at some point the leaked-through noise should be bearable. On top of that, she intends to use as much of the absorbed power for propulsion as she can get away with.

She can almost hear her triple-redundant quantum computer crunch (or should it beep?) as it performs the necessary calculations. Four membranes should do the trick, yet she has enough material for five. So five it’ll be.

But if those membranes rupture—especially the outer ones at the stupendous sound pressures they must produce—enough high dB noise can leak in that can either kill or seriously wound her or the Moiety Alien. So she’d better prepare an army of nano-repair bots in between all these layers to constantly repair cracks and ruptures. Well, at least they’ll have enough sound energy to vibration-weld with.

Finally, the triple electrostatic loudspeaker membrane (ELM) shield has to be flexible, so that—for example—she can dive in first into this hypersound inferno with the forward half of the enveloping ELM shield around her, followed by the Moiety Alien in the other half. And vice-versa if—hopefully when—they can exit this insane layer.

And sound waves also disperse in air. So could she run away from them? Two problems with that—the speed of sound in air, and the amount of dispersion. The sound waves will come at her at Mach 1, or one thousand and two hundred and twenty-four kilometers per hour. She just can’t fly that fast. And the dispersion at the maximum possible pressure is too slow. Records of the Krakatau explosion in 1883 measured 172 decibels at 160 kilometers from the erupting volcano (assuming it produced the full 194 dB at its very center). That covers about 90% of this layer.

So she can’t run and she can’t hide. She and her alien companion must face the tremendous sound waves head-on and hope their ELM shield works and keeps working.

Then the next, possible disastrous notion, strikes her. The thickness of each layer, so far, is 13.75 kilometers (at some point this regularity must break down, or the Core is only 8 kilometers across). To the best of her knowledge, the barriers between the layers are impenetrable to sound, as well. So they can act as echo chambers, meaning that the wavefront of sound that she has just successfully passed through might be reflected at her—even if at a somewhat lower sound pressure—a bit later on. Or not just at her back, but from her sides, and from above and below. From basically any direction. Even without reverberations, the sound wave would complete a full round trip—say 151 km on average—about every 7 minutes and then would have a dispersion of about 15 dB per round trip.

Holy smokes, Na-Yeli quickly calculates, six times of being hit with the same sound wave—every 7 minutes—before it dampens below the pain threshold. And that without taking into account the reverberations of that stupendous sound wave against the globular barriers of this penultimate layer

On the sunny side, that same sound wave should clash with itself, and reflections of itself, which would be mostly out of phase with each other. It’ll be a myriad of sound waves, the original mixing with itself and its echoes until it finally disperses and smothers itself—even while occasionally re-amplifying parts of itself back to 194 dB (as higher is impossible). On average forty-two minutes before the original sound wave has dampened below the pain threshold of 130 dB.

In any case, she does not only need scouting probes in front of her, she needs to be enveloped in a cloud of probes. Even as sturdy as she can make them, some will still fail, so she needs plenty for backup. In a flash of foresight, she’d cloned a lot of Kittis on their route to the North Pole in the Berserker Forest layer, figuring she should do that while she had the time and opportunity. Now she’s glad as she can use them all for her Soundcloud of Kittis as pre-detectors, all attached to the forward part of her ELM shield in order to get all that non-biological matter through the semi-permeable membrane.

—or—

Author’s note: sometimes, indeed, only fools jump in. Now Na-Yeli must make a lot of preparations before she can even think of entering this extremely dangerous layer. And once she does, what will she and her alien partner-in-discovery find? Stay tuned!